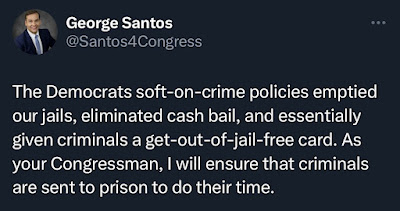

the WHICH hunt will continue.

Which case will he lose next?

AND THE HITS JUST KEEP ON COMIN'

Oopsie:

We fixin' to run outa popcorn... OK, George, look on the bright side. Maybe you won't have to have a cellie, there'll be so much spare bed space courtesy of the Democrats.

UPDATE

OK, CLASSMATES, RECESS IS OVER

Back onto real-world exigent topics. First, another excellent new read:

Science doesn’t sit very comfortably in American society. Some of us believe that it’s the foundation of social progress and national security. They worry that we aren’t doing enough to support it, that we are failing to invest in research that will improve our lives and spur innovation to compete with our adversaries around the globe for military and economic dominance. Others are convinced that science is leading the country astray, believing that scientists routinely push suspect medical treatments on the public, make politically biased recommendations, or, in the case of global warming, have engineered a hoax of proportions never before seen. Science often seems trapped in a never-ending game of king-of-the-hill with advocates forever boosting science toward the top—seeking to expand its status and influence inch by inch—and skeptics trying equally hard to knock it down in the eyes of the public. It’s an odd relationship to be sure.

The cultural struggle over the place of science in our lives isn’t new. There have always been science boosters among us. The truth is that nearly 75 percent of the public is firmly behind science, believing that its benefits outweigh any harms. But there have always been detractors too. Long before the climate-change and COVID-vaccine skeptics, there were the anti-vaccination societies in the late nineteenth century, opposition to science in the 1930s based on its perceived immorality, and a prominent anti-drinking-water-fluoridation movement in the 1950s, among others.

It seems that the detractors have gotten the upper hand of late…

Rudolph, John L. Why We Teach Science (pp. 14-15). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition.

I cited an earlier book by Dr. Rudolph in a prior post, "Define 'Science'."

OK, science education needs to step up its game, ja"

Build a Science Education Based on EvidenceYeah. "Define 'Evidence'."

The foundation of science is its commitment to the evidence of our senses, that the hypotheses, theories, and conjectures scientists come up with are all eventually tested by comparing them to what happens in the world. However, we continue to allow a whole series of untested working hypotheses guide students’ experiences in science classrooms across the country.Yet, the problem remains that we have no hard evidence to support any of these assumptions or working hypotheses about science education—certainly not for the science education we currently have or even that the latest policy initiatives aspire to. It seems beyond comprehension that the overwhelming majority of scientists and science educators continue to maintain their commitments to these faith-based positions without seeking evidence that would support or refute them…

- We assume that learning the scientific accounts and explanations of various aspects of the world—of phase changes, heat transfer, species variability, or human immune response—will enable us to make better everyday decisions.

- We imagine that engaging in the process of science—doing labs, collecting water samples, or measuring daily temperature and humidity—will help us think critically and reason logically in our day-to-day affairs.

- We accept—even double down on—the belief that raising standardized test scores and increasing Advanced Placement enrollments will spur technological innovation and lead to national economic prosperity.

- And we feel in our hearts that those higher science test scores and the repeated immersion in science laboratories will somehow translate into a public willing and able to intelligently debate and come to enlightened policy decisions about some of the most challenging science-related challenges of our time.

… I’ve tried to point out the flaws in these assumptions. There is plenty of evidence to draw on from a variety of sources, including the fields of developmental psychology, science communication, cultural cognition, economics, sociology, history, and corners of science education. And we have data from agencies such as the Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the National Center for Education Statistics, and even from our own experience—if we stop to reflect on it—to help us see the situation before us. We only need to use this knowledge of how education works, how people make sense of the world around them, and how they interact with others individually and collectively to create the kind of science education we desperately need.

… There is plenty of evidence, in fact, that what we’re currently doing is making things worse, that what we’re doing, while seeming to meet pressing societal needs, is actually making it harder for science to grow and thrive as an essential part of our culture. What I’ve laid out in these pages is a reason to change, a reason to do something different from what we’ve been doing for the past sixty years or so. My only hope is that we begin to really think about why it is we think science education is so important to our future and work to create a science education that will realize that vision—that is, to think about why it is we teach science, and why we should. [John Rudolph, pp. 181-183]

__________

No comments:

Post a Comment