This book had not been on my radar. Then I read a lengthy article in Harper's by the book's author, Dr. Jason Blakely. Fortunate to have run across these. Both the article and the book are outstanding.

I'd been familiar with the term "hermeneutics," but after reading the book I had to admit we'd given the topic significantly short shrift in grad school, sufficing to note its application in "interpretations" of theological writings. Our Bad.

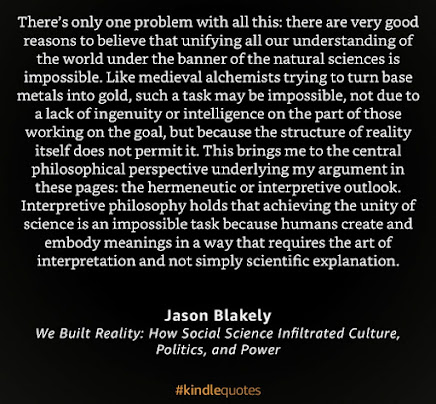

...Indeed, a culture of scientism helps produce a culture that also rejects genuine scientific authority. The scientism studied in these pages, by falsely trading on an authority it does not wield, helps to sow a wider skepticism and cynicism about the “elite” voices of scientists as such. A disturbing increase in science denial (e.g., conspiracy theorists, anti-vaxxers, climate change deniers) is in a mutually supporting dialectic with the absolute scientism of a Pinker or a Dawkins. Although they have not yet realized it, figures like Pinker and Dawkins, far from defending science, undermine it by overpromising and exaggerating its authority. Ultra-Darwinists and biblical literalists are dance partners.

The only way out of this dilemma that does not involve the dual irrationalisms of rejecting science and inflating the authority of science beyond reasonable bounds involves recovering other ways of knowing the world. One of the chief resources in this regard is the humanities. The humanities insist that there is an art to interpreting human behavior that is never reducible to a strict or exact science. Although it is not scientific, this art is not subjective or arbitrary, either. Rather, it is an art practiced by many historians, literary scholars, cultural theorists, and even some rogue social scientists. Only the art of interpretation can begin to restore our culture to a clearer form of self-understanding that escapes the current delusions and disappointments of our reigning scientism. Only this will help correct the frightening tendency in our present hour to reject the rightful authority of natural science (e.g., ecology, vaccines) while at the same time submitting uncritically to the scientism of popular social theories (e.g., broken windows, Homo economicus). In the past of the humanities and interpretive disciplines lies a new future. But a key question remains: Where are the new humanists?

Blakely, Jason. We Built Reality (pp. 135-136). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

I've long tended to bristle at the word "scientism." I'm now pretty much over it. Pretty much.

INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Nice. Very nice. And I'm not even a "religious" person (fully recovered Episcopalian, subsequent dilettante UU, Zen-leaning dude).

Goes to my recurrent focus on "Deliberation Science."

THE HERMENEUTICS OF "BLADE RUNNER?" WHAT?

Stsy with me here...

In this regard, a far better proposal for evaluating AI than the Turing test is suggested by the science fiction classic Blade Runner. This film—based on a novel by Philip K. Dick—opens with a scene depicting an interview in which a human is testing for the presence of AI. The test requires determining whether an android (known in the movie as a “replicant”) is capable of empathy. Empathy is a state that involves an awareness of how another person is experiencing a situation: what matters to him or her and what the emotional significance of a set of circumstances might be. This is closer to the criterion for human intelligence that Searle calls “semantics” and Taylor the “significance” factor. A reworked Turing test would need to be able to determine if an agent were experiencing significance or meanings. Such a test would be an interpretive or hermeneutic threshold for intelligence.Yeah. That's one of my all-time favorite flicks.

Blade Runner also serves as a powerful interpretive fable for the anxieties surrounding technological society. Taking place in a future version of Los Angeles, the plot follows a man named Deckard, whose profession is “blade running,” or hunting and destroying rogue replicants. Yet Deckard finds himself increasingly disturbed and alienated not only by his own severe loss of empathy for those around him but also by the atomized social relations of an impersonal, consumer society dominated by distant corporations. In this setting an awakening of empathy comes from a strange place: Deckard falls in love with one of the replicants he has been hired to kill.

At the center of this story is a deeper cultural fear that is the actual, repressed object of anxiety in the contemporary AI debate between doomsayers and boosters. This is a repressed fear of ourselves and what we might become if we go further down the road of the form of selfhood presented by Homo machina. That is to say, fear of robots is fear of ourselves without humanity, without empathy. Or perhaps more accurately, fear of AI is fear not of technology but of a new constellation of meanings opened up by technological society. The machine-self is one possible form of identity that humans embody in a culture of scientism.

This in turn might be linked to the distinctively modern cultures of violence—as scientifically planned by military experts and technocrats—so common in societies across the ideological spectrum. Consider in this light Joseph Stalin’s conviction that social science had revealed society could be explained “in accordance with the laws of movement of matter.” This machine view of society was the prologue to treating people like basic parts, to be replaced with other purportedly better parts. Stalinism was only one extreme version of the propensity of modern societies to conduct “scientific” mass killings. This is the kind of killing carried out remotely and planned by scientific experts. A dark dream that began in the French Revolution with the guillotine has reached an apotheosis with the invention of the concentration camp-laboratory, where violence is perfectly justified because it is perfectly rational. There is no “I” behind the system of violence in the camp-laboratory; neither is there a “you” on the receiving end. In the last analysis, there is only the impersonal mechanics of a machine grinding humanity into cinder and fire.

In Blade Runner we are offered a capitalist version of this mechanistic culture of violence and antihumanism. The humans who populate a future, dystopian Los Angeles have become radically more robotic in this way; they are no longer attuned to the experiences of their neighbors and are willing to treat them like mute objects. The streets of this Los Angeles are filled with a babble of tongues, homeless people dig through the trash, and crowds rush through the sidewalks distracted by their own individual market activity. No one speaks to one another, while neon advertisements shout platitudes about enjoying soft drinks or starting a new life on an “off-world” colony in outer space. Deckard at one point remarks that his ex-wife used to call him a “cold fish,” but the audience is relentlessly confronted with an entire society of cold fishes. What distinguishes Deckard is that he struggles mightily throughout the film to overcome his hardened willingness to assassinate others as simply part of his job, a mere market transaction. The entire plot is thus absorbed in the problem of the loss of human empathy and its replacement with a roboticized self that sees all relationships—even those of violence—as mechanical and rational. In all these ways, the city and inhabitants depicted in Blade Runner are not a portrait of the future at all but a dramatic picture of the present: the world as built by Homo machina. [Blakely, pp. 66-69].

Buy Jason's book. You're welcome in advance.

More to come...

__________

No comments:

Post a Comment