The critics are again piling on.

In the early days of EMRs, the pioneers like Intermountain, Vanderbilt, Duke, and Partners differentiated themselves by developing their own proprietary EMRs and then using them in a meaningful way, without any financial incentive except their own to do so. Meaningful Use Stage 1 served a valuable purpose; it jump-started the adoption of commercially supported EMRs in an industry that needed jump-starting. Maybe we should cancel Stage 2 and Stage 3, spend some of that money to seed true innovation (think DARPA for healthcare IT), and let survival of the fittest play a role in deciding which organizations will utilize their EMRs, and subsequent data, most effectively to improve healthcare.

From

"Is It Time To Eliminate Meaningful Use?"

"Spend some of that money to seed true innovation"?

Seriously?

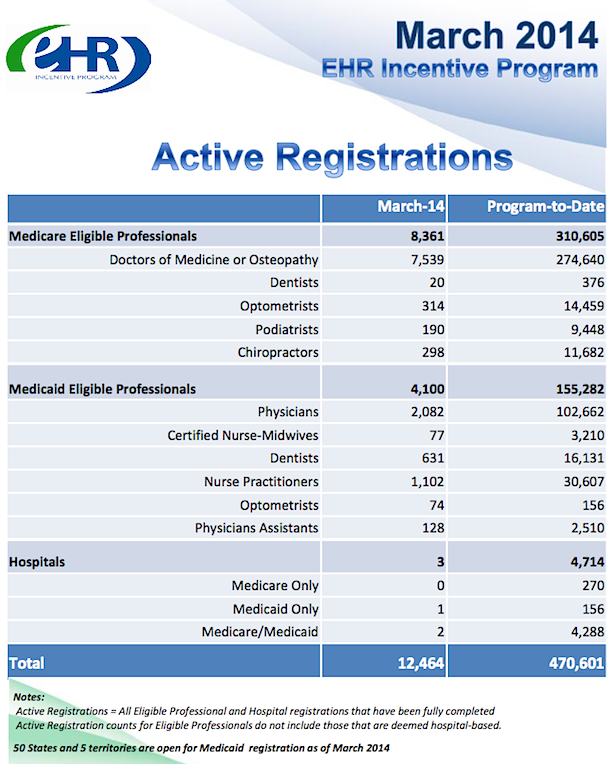

What money? In case you've not been paying attention, the bulk of the MU money has already been dispensed, with the largest proportion of the relatively little that remains earmarked for late-adopting Stage 1 participants. You're not going to "seed" anything of substance on a national scale with remaining MU funds.

Do people even

listen to what they're saying?

OUTCOMES MEASURES, ANYONE?

Process measures like Meaningful Use,

CQMs, PQRS, etc, as I've noted before, are tangential

proxies for effectiveness in health care. It's assumed that if you are doing and reporting on X, Y, Z, A, B, C, D, E, and F, improved outcomes will eventually follow.

How about if we lay on a concerted effort to measure

actual outcomes directly? And, in that regard, a1c (the gamut of lab results, actually), BP, BMI, etc are themselves still

proxies, not "outcomes" in terms of end-results health.

Virtually

every dx of a suboptimal medical/health condition has an associated prognosis and tx plan (the "P" component of the "SOAP") aimed at improved outcome/resolution (even if it's sadly limited to the palliative for the fatal dx's). We should be mapping realistic interim and end-state "outcomes" goals to

every dx. Some will be simple, others maddeningly complex and often problematic. But, without them, we will simply continue to argue endlessly and fruitlessly about health care effectiveness and "value."

Time to seriously get off the dime.

AHRQ website, on "outcomes" -

What is outcomes research?

Outcomes research seeks to understand the end results of particular health care practices and interventions. End results include effects that people experience and care about, such as change in the ability to function. In particular, for individuals with chronic conditions—where cure is not always possible—end results include quality of life as well as mortality. By linking the care people get to the outcomes they experience, outcomes research has become the key to developing better ways to monitor and improve the quality of care. Supporting improvements in health outcomes is a strategic goal of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research).

The urgent need for outcomes research was highlighted in the early 1980s, when researchers discovered that "geography is destiny." Time and again, studies documented that medical practices as commonplace as hysterectomy and hernia repair were performed much more frequently in some areas than in others, even when there were no differences in the underlying rates of disease. Furthermore, there was often no information about the end results for the patients who received a particular procedure, and few comparative studies to show which interventions were most effective. These findings challenged researchers, clinicians, and health systems leaders to develop new tools to assess the impact of health care services...

Measuring Outcomes

Historically, clinicians have relied primarily on traditional biomedical measures, such as the results of laboratory tests, to determine whether a health intervention is necessary and whether it is successful. Researchers have discovered, however, that when they use only these measures, they miss many of the outcomes that matter most to patients. Hence, outcomes research also measures how people function and their experiences with care...

Future Directions

No longer just the domain of a small cadre of researchers, outcomes research has altered the culture of clinical practice and health care research by changing how we assess the end results of health care services. In doing so, it has provided the foundation for measuring the quality of care. The results of AHRQ outcomes research are becoming part of the "report cards" that purchasers and consumers can use to assess the quality of care in health plans. For public programs such as Medicaid and Medicare, outcomes research provides policymakers with the tools to monitor and improve quality both in traditional settings and under managed care. Outcomes research is the key to knowing not only what quality of care we can achieve, but how we can achieve it.

OK. In the same vein, how about this, from

Academy Health,

HEALTH OUTCOMES RESEARCH: A PRIMER (pdf):

What is outcomes research?

Outcomes research studies the end results of medical care – the effect of the health care process on the health and well-being of patients and populations. It spans a broad spectrum of issues from studies evaluating the effectiveness of a particular medical or surgical procedure to examinations of the impact of insurance status or reimbursement policies on the outcomes of care. It also ranges from the development and use of tools to measure health status to analyses of the best way to disseminate the results of outcomes research to physicians or consumers to encourage behavior change.

The field of outcomes research emerged from a growing concern about which medical treatments work best and for whom. In large part because of its potential to address the interrelated issues of cost and quality of health care, public and private sector interest in outcomes research has grown dramatically in the past several years...

The Setting It Studies

Outcomes research evaluates the results of the health care process in the real-life world of the doctor’s office, hospital, health clinic and even the home. This contrasts with traditional randomized controlled studies, funded mainly through the National Institutes of Health, which test the success of treatments in controlled environments. These are called efficacy studies. Research in real-life settings is called effectiveness research.

The Health Status Measures It Uses

Traditionally, studies have measured health status, or health outcomes, in terms of physiological measurements – through laboratory test results, complication rates (e.g. infections) or death. These measures alone do not adequately capture health status. A patient’s functional status, well-being, and satisfaction with care must compliment the traditional measures...

That was published in

1994, twenty years ago. What are we waiting for? While I don't underestimate the difficulties involved with establishing standardized "operational definitions" of outcome measures, it is not impossible. Surely adding uniform, basic quantitative progress/outcomes metrics to the "Active dx" lists now a requisite staple of certified EHRs is do-able.

"Innovation," anyone?

THE CLINICAL PROCESS AND "PDSA"

We refer to the "SOAP" process, documented in the "SOAP note" now firmly in the center of the EHR.

- Subjective;

- Objective;

- Assessment;

- Plan.

The subjective and objective data (including those comprising the relevant aspects of FH, SH, PMH, Active Rx, Active dx, HPI, ROS, Vitals, Labs, PE) converge to underpin the physician's "assessment" (dx) and resultant "plan" (Rx/tx/px) for mitigating (or curing) the patient's current problem(s) and arriving at better health (the desired "outcome" from the patient POV).

As my HealthInsight Sup Keith Parker (an astute, Harley-riding former Special Forces medic) always liked to admonish, there should be an explicit "E" (evaluation) at the end of the traditional SOAP model. My quickie Photoshop visualization of the process cycle:

In terms of the PDSA improvement model,

S,

O, and

A of "SOAPE" comprise the PDSA planning phase (you plan based on the analytic aggregation and synthesis of your current data), the "Plan" (

P) is the PDSA "Do" phase, the "Study" is the "

E" of SOAPE, and, -- most often -- recursively, we subsequently revisit the "

A" (assessment" phase) of SOAPE. Did we hit the mark or not? If not, what next? The "Act" of PDSA.

Fundamental to experimental science broadly is the

explicit statement of the empirical (quantitated) goal in the planning phase, answering the question "what will constitute a 'significant' improvement

vis a vis the

status quo?" You don't get to run an experiment and

then arbitrarily decide whether you've "improved" things or not.

Maybe that's "the

'art' of medicine," but it's not science.

4/28 UPDATE

Doctors Should Be Paid for Outcomes. But Which Outcomes?

By HANS DUVEFELT, MD

Should we be paid for outcomes?

This is often proposed, but I have trouble understanding it. Real outcomes are not blood pressure or blood sugar numbers; they are deaths, strokes, heart attacks, amputations, hospital-acquired infections and the like.

In today’s medicine-as-manufacturing paradigm, such events are seen as preventable and punishable.

Ironically, the U.S. insurance industry has no trouble recognizing “Acts of God” or “force majeure” as events beyond human control in spheres other than healthcare.

There is too little discussion about patients’ free choice or responsibility. Both in medical malpractice cases and in the healthcare debate, it appears that it is the doctor’s fault if the patient doesn’t get well.

If my diabetic patient doesn’t follow my advice, I must not have tried hard enough, the logic goes, so I should be penalized with a smaller paycheck.

The dark side of such a system is that doctors might cull such patients from their practices in self defense and not accept new ones...

Vik Khanna responds.

___

More to come...