My late Mother's younger sister Edna died last year at age 90. She left her house in Elmont, where she'd lived since I was a kid, equally to my sister and I and one of her long-time home caregivers. We'd had no idea. My sister is acting as Executor. She got notice several weeks ago of a lien placed against the property (we have it on the market, and there is a buyer pending) by NY Medicaid for about $89,000 in "claw-back" monies for Edna's recent end-of-life hospital care. Interesting. The aged little house is so out-of-code it probably needs to be bulldozed. The property is really only worth what the lot will bring. When the state and the lawyer are finished with us, there won't be much net to divide.I actually grew up in northern New Jersey -- Morristown, East Hanover, Somerville, each about 30 miles or so out of Manhattan. My late Dad worked his entire civilian career for Bell Labs, first at Murray Hill, then Whippany. Semiconducters R&D. Geeky, pocket protector kind of guy. I come by it honest.

In November 2013 I covered the NYeC 2013 Digital Health Conference (see here as well). New York is in fact doing great things in the healthcare space.

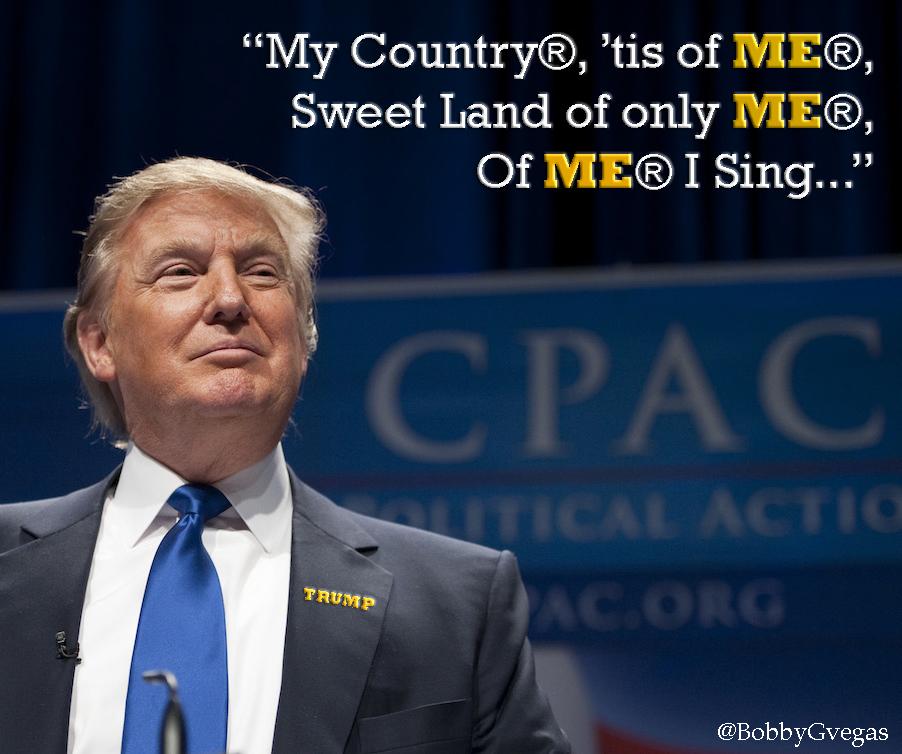

NYC's most visible (and audible) resident has been making all manner of waves of late. As reported by Politico,

Billionaire businessman Donald Trump on Wednesday offered a glimpse into his presidential platform on healthcare, saying he would replace ObamaCare with “something terrific.”I've started a new initiative on Twitter called "Your Daily Donald™"

“It’s gotta go,” Trump said of ObamaCare in an interview Wednesday with CNN. “Repeal and replace with something terrific."

Mostly quickie Photoshop jabs at this incoherent, narcissistic, garrulous blowhard.

Dude is "terrific." Just ask him.

Whatever. The first GOP "debate" on Thursday will be, well, Pass The Popcorn.

UPDATE: from PolitiFact, "Is Donald Trump still 'for single-payer' health care?"

__

Back to reality. Having just finished Steve Brill's fine book "America's Bitter Pill" (see my prior post), I looked about online to see what, if anything, was new with David Goldhill, cited in Brill's book (and whom I'd cited on another blog back in 2009).

Paydirt.

An edited compilation. Truly a bargain on Amazon at 99 cents, Kindle edition. Seeing the private-markets-are-a-panacea "American Enterprise Institute," "The Heritage Foundation," and "The Manhattan Institute" cited required a bit of "check-your-dubiety-at-the-door." Proved worth the effort.

ForewordThey had me at "Fragmentation."

Denis A. Cortese, MD

Robert K. Smoldt, MBA

A patient facing a serious or life-threatening illness needs an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. The same is true for the U.S. health care system. America’s health care costs per person and as a percentage of its economy are the highest in the world, threatening the long-term solvency of U.S. states and the federal government. Despite such outsize spending, patient outcomes, safety, and access to appropriate care are too often disparate and inconsistent. The good news: for a variety of reasons, many of the system’s key players appear ready to make fundamental changes that will move the U.S. to higher-value health care.

...When calculating value, cost is perhaps the factor most likely to be misdiagnosed. Some observers believe that simply lowering the amount paid for various services (per physician visit, per lab test, per imaging test, per surgery, etc.) will solve America’s health care cost problem. Yet decades of experience reveal that low-deductible health insurance and price controls do not reduce total spending. If anything, the opposite is true...

New York’s Next Health Care Revolution: How Public and Private Employers Can Empower Patients and Consumers offers a bold new approach by recognizing that reforms need not only happen at the national level; local changes, spurred by government and the private sector, can also lead to significant improvements. The essays herein are equally infused with a justified dose of optimism: reform efforts, thanks to a confluence of factors, including the Affordable Care Act and a growing number of effective, private-sector health care experiments, are beginning to spur the changes necessary to make the delivery of high-value health care the cornerstone of American medicine...

Rethinking the state’s role in competition—from regulating insurance to encouraging nimble new competitors who can re-bundle health care services (via telemedicine and direct contracting, for example)—can lower costs and launch virtuous cycles of value-focused innovation.

The key to bringing more value to patients is to introduce incentives that reward the provision of high-value care. Patient-centered reforms— including greater transparency, private exchanges, and value-based payment and benefit designs—will likely unleash a wave of positive change that grows in force over time. Of

As Joseph Antos explains in Chapter 2: “Payment reform can discourage the fragmentation and overutilization that has defined fee-for-service contracts to date, while encouraging innovation and competition in the delivery of care.”

Indeed, when we pay for value, we’re more likely to get it. By channeling competition at the level of the patient-consumer, we can ensure that the providers who deliver the best value to patients will be rewarded, creating demand for yet more innovation.

(2015-05-20). NEW YORK'S NEXT HEALTH CARE REVOLUTION: How Employers Can Empower Patients and Consumers (pp xi - 1). Manhattan Institute. Kindle Edition.

A patient facing a serious or life-threatening illness needs an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.Well, in my case, I think I now have the former and will soon begin the latter. But, getting there has neither been simple nor easy. I know: 'welcome to the club.'

We'll triangulate this book with Brill's and Elhuage's and a number of relevant others I've already cited as this post progresses.

FragmentationInterestingly, search through Steve Brill's book and the variants of the word "fragment" are nowhere to be found. But, then, "America's Bitter Pill" is mostly a history of the byzantine politics of the enactment of the PPACA and the subsequent Healthcare.gov launch debacle.

Highly competitive on nearly every other front, New York, like most other states, is astonishingly accepting of huge pricing disparities in health care. Consider the following 2012 tale of two Manhattan hospitals: at the public Metropolitan Hospital, the bill for a patient discharged with a heart attack (diagnosis-related group code 280) was $22,000; at the nearby private Lenox Hill Hospital, it totaled $112,000.14 New York is not alone. In Philadelphia, the price of echocardiograms (ultrasound images of the heart) ranged from $700 to $12,000, according to the New York Times...

New York’s unusually high costs are explained, in part, by the fact that its medical landscape is marked by fragmentation and little vertical integration, which means few incentives for providers to control expenses. Certain other states, by contrast, have large medical groups and integrated systems, such as Kaiser Permanente. Located in California, Colorado, and Georgia, among others, Kaiser owns all the hospitals and employs all the doctors in its network, thereby maintaining tighter control over costs and quality... [ibid, pg. 24].

Searching on the loosely synonymous "coordinate" yields only a few weak results such as

Notably, the June 16 speech contained none of Obama’s campaign trail attacks on the drug companies or insurers. Instead, the president promised savings that could come through better electronic medical records, more efficient use of prescription drugs, and more coordinated care overall...With respect to Health IT, "New York's Next Health Care Revolution" gives us the predictable stuff we've all been hearing for years:

Brill, Steven (2015-01-05). America's Bitter Pill: Money, Politics, Backroom Deals, and the Fight to Fix Our Broken Healthcare System (Kindle Locations 2052-2054). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Interoperability would break down health systems’ “walled gardens” that have trapped information on quality and outcomes within individual systems. Interoperability would incentivize competition among insurers, too, by easily allowing consumers to take their health care information with them when switching plans. (Given robust competition on state health insurance exchanges to become the benchmark plan for federal premium subsidies, many consumers will likely switch plans annually to keep premiums down.)Yeah. The "Interoperability Is Good" riff.

Interoperable health records would reduce wasteful duplication of tests and needless paperwork, improving continuity of care. Interoperable electronic health records (EHRs) would spur medical research by allowing data-analytics platforms to scan millions of records to identify disease patterns, predict and prevent adverse events, and advance the most effective treatments for specialized groups of patients. Indeed, as genomic data and targeted therapies for complex chronic ailments become routine, interoperable EHRs represent the future foundation of precision medicine. [op cit, pg 74].

Progress remains slow and halting. "Interoperababble" remains the norm, given the continuing competing incumbents' private market margin imperatives of opacity.

Maybe it'll be API's to the rescue. Eventually.

BTW, interesting that "Oscar Health" is cited in both books. Fascinating young company.

Brill on obstacles to the way forward, in a series of self-posed questions and answers:

STUCK IN THE JALOPYIt's a long, thoughtful chapter. Mr. Brill (himself a New Yorker, btw) basically argues for heavily regulated private market competition under a vertical and horizontal "public utility" model (very similar to a number of our EU counterparts). Think a bunch of Kaisers all doing battle on patient-centered quality of care.

THIS IS THE PART WHERE I AM SUPPOSED TO TELL YOU WHAT I MAKE of all this— what the Obamacare saga really means, what it portends, and what we might do about it.

First, the easy stuff that I was thinking about as the enrollment returns came in on March 31, 2014.

Do I wish that the National War Labor Board had ruled in 1943 that health insurance benefits did, in fact, count as wages and, therefore, that adding them would not be allowed under the wartime wage control regulations?

Sure. Along with the follow-on decision by the IRS that insurance benefits could be tax free, that was the fork in the road that set the United States off in the wrong direction— putting employers on track to be the primary providers of health insurance. That is a different path from that taken by every other developed country, all of which produce the same or better healthcare results than we do at a far lower cost. Without employers offering insurance to workers, the pressure on politicians to provide a public program would have been unstoppable.

America’s dysfunctional healthcare house, with the bad plumbing and electricity, leaky roof, broken windows, and rotting floors, would never have been built and become so entrenched in its special interest foundations that it could not be torn down. We would have never been stuck with the broken-down jalopy that we could only repair piecemeal. Pick your favorite metaphor for the hurdles faced by reformers for the past seven decades... [Brill, op cit, Locations 6546-6559].

The first regulation would require that any market have at least two of these big, fully integrated provider– insurance company players. There could be no monopolies, only oligopolies, as antitrust lawyers would call them. The larger markets, such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, might have to have four or five or even more players to make the competition real and to make sure, with accompanying regulatory requirements, that their footprints were big enough and their marketing plans robust enough to serve patients throughout their regions, not just in the wealthier areas. [ibid, Locations 7033-7037].I've thoroughly enjoyed -- and highly recommend -- both books. Would love to get JD Kleinke's take on all of this.

Also, in light of some of Steve Brill's recommendations for physician-led organizations as part of effective reform, another book I've cited comes to mind. See my post "Physician, Heal Thy System."

apropos of this theme, a number of other works come to mind. e.g., Jonathan Bush's "Where Does It Hurt," Vik Khanna's "Your Personal Affordable Care Act," and Jed Graham's "Obamacare is a Great Mess," to cite just a few I've reviewed.

I guess the thing that bothers me most about "New York's Next Health Care Revolution" is -- aside from its unwavering faith in private markets -- its advocacy of continuing employers as the principal intermediaries for the provision of health insurance for the bilk of the civilian population (including via the vehicle of "private exchanges"). Elhauge has long argued cogently for the de-coupling of health insurance from employment.

As I see it, the strength of the market paradigm are the standard ones: if consumers are knowledgeable, have similar resources, and have incentives to trade off the benefits and costs of each product, then market competition promotes productive efficiency, accommodates varying consumer preferences, and achieves allocative efficiency. The problem of unequal resources is largely external to the market paradigm and potentially remediable through vouchers. But the more fundamental problem of the healthcare market flows from an inherent division between knowledge and incentives. Unlike other markets no decisionmaker exists who has both the knowledge and the incentives to decide when the costs of supplying a particular good or service exceed its social value. Patients lack the knowledge and, even the fact that others (such as insurers or employers) cover much of the social costs, also generally lack the necessary incentives. Physicians and other healthcare providers are knowledgeable about medicine but not about social benefits and costs. Moreover, under current American market systems they either have incentives to provide too much care (if paid on a fee-for-service basis) or incentives to provide too little care (if paid on a capitation basis). Insurance plans generally lack the information to make case-by-case cost than if it decisions and have incentives to provide two little care, or to select for low-risk enrollees unlikely to need much care, because the insurers pay the cost of health care but do not enjoy its benefits…That was 1994, in "Allocating Health Care Morally," which I cited in 2009 in my post "The U.S. health care policy morass." Elhauge goes on to explicitly advocate taking employers out of the health insurance business.

To ground my analysis, let me assert up front a concrete proposal, one toward which I believe the national health care systems of the world are (from different directions) slowly converging. The analysis of the moral paradigm offered here supports, when coupled with the strengths and weaknesses of the other paradigms, a health care system having the following elements.A generation later, we still retain the core notion of employer-based health insurance, notwithstanding that average length of employment tenure continues to decline, with all of the administrative churn it inexorably brings.

- A politically set annual health care budget with an associated tax not linked to employment [emphasis mine].

- Free access for all individuals to a care-allocating plan.

- Individual choice about which plan they wish to join for some significant period (I suggest three years).

- Competition among care-allocating plans that each receive a share of the government budget based on the number of individuals they enroll, adjusted for each person's health risk, and that cannot retain profits from their budget (other than a possible bonus linked to total number of enrollees) but must instead spend it on those enrollees. Plans must accept all who wish to enroll... [pg 1453]

One last Elhauge swimming-against-the-tide observation:

An egalitarian distribution of health care is less likely to undermine productive incentives than an egalitarian distribution of cash, food, clothing, or shelter. People do not want to be sick, and (leaving aside hypochondriacs) have no desire for health care unless they are sick. There is thus no incentive to stay sick in order to get health care. In fact, getting well eliminates the need. Nor does the distribution of health care greatly reduce the incentive to work since working is still necessary to buy the basics in life. Moreover, the concern about work disincentives is weaker for sick individuals because illness often disables one from working anyway... [ibid, pg 1488].__

DAVE CHASE ON LINKEDIN

Are We Seeing the First Stages of a Velvet Medical Revolution?A good read.

It is only after a revolution happens that one can clearly look back and see what triggered the revolution.Generational discontinuities and external factors such as technology shifts can create the conditions for a revolution where it may not have been possible before. Consequently, I think we may be seeing a revolution’s first phase happen before our eyes.

I’m convinced that the only way there will be a true revolution in healthcare is if there is a partnership between individuals (aka patients/consumers/people) and clinicians. One without the other won’t get the job done. However, I feel doctors will play a catalyzing role. As I’ve been a Johnny Appleseed of sorts chronicling the far-reaching and transformational work of doc-entrepreneurs, it feeds my optimism that it’s possible to overcome the Preservatives who have 3 trillion reasons to protect the status quo...

SHARDS UPDATE

August 4th. My urology clinic is maddeningly non-communicative. Not even an email address link on their website. A staffer called me today in response to repeated messages I left. Now I'm told that they cannot do my Calypso beacons implant px until August 18th, and I have to go to their Oakland facility for the procedure. This will effectively put the onset of my IMRT tx off until probably September. I posted a secure message on my RadOnc clinic's new (and clunky) portal.

Dear Xxxxxx Xxxxxxx Oncology & Hematology,

I am experiencing a lot of delay with XxxXxx Urology regarding the Calypso beacons implant px you ordered. They are difficult to communicate with, and slow to act. Today a staffer called me back to say they will now not be able to do this procedure until August 18th, which will set me back likely until just about September to begin my IMRT tx.

Given the indeterminacy of the aggressiveness of my prostate cancer, should I be worried over this?

It seems problematic now; trying to find another urologist to do this may not speed things up.

Any advice?

Sincerely,

Robert GladdI continue to be fragged.

__

PS: YOUR DAILY DONALD™

Seriously, America? Below, transcript of a recent live Trump response to a questions about the contentious proposed Iranian nuclear agreement.

"Look, having nuclear—my uncle was a great professor and scientist and engineer, Dr. John Trump at MIT; good genes, very good genes, okay, very smart, the Wharton School of Finance, very good, very smart—you know, if you’re a conservative Republican, if I were a liberal, if, like, okay, if I ran as a liberal Democrat, they would say I'm one of the smartest people anywhere in the world—it’s true!—but when you're a conservative Republican they try—oh, do they do a number—that’s why I always start off: Went to Wharton, was a good student, went there, went there, did this, built a fortune—you know I have to give my like credentials all the time, because we’re a little disadvantaged—but you look at the nuclear deal, the thing that really bothers me—it would have been so easy, and it’s not as important as these lives are (nuclear is powerful; my uncle explained that to me many, many years ago, the power and that was 35 years ago; he would explain the power of what's going to happen and he was right—who would have thought?), but when you look at what's going on with the four prisoners—now it used to be three, now it’s four—but when it was three and even now, I would have said it's all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don't, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years—but the Persians are great negotiators, the Iranians are great negotiators, so, and they, they just killed, they just killed us."Terrific.

___

More to come...

No comments:

Post a Comment