NOW REPORTING FROM BALTIMORE. An eclectic, iconoclastic, independent, private, non-commercial blog begun in 2010 in support of the federal Meaningful Use REC initiative, and Health IT and Heathcare improvement more broadly. Moving now toward important broader STEM and societal/ethics topics. Formerly known as "The REC Blog." Best viewed with Safari, FireFox, or Chrome. NOTES, the Adobe Flash plugin is no longer supported. Comments are moderated, thanks to trolls.

Search the KHIT Blog

Tuesday, August 31, 2021

Sunday, August 29, 2021

16 years after Hurricane Katrina

When Katrina hit, my wife was Environmental Division Director of Quality for Baton Rouge-based Shaw Group. They were quickly awarded a number of (somewhat controversial) remediation contracts (they were the company that pumped NOLA "dry," ran the blue tarp roofing program, and administered the FEMA trailer complexes).Cheryl subsequently spent the rest of the fall down in Baton Rouge and NOLA (we were living in Vegas at the time), where her crews worked 16-20 hours a day, 6-7 days a week. IIRC, I saw her for all of 11 days between Katrina and Christmas...

Saturday, August 28, 2021

Parse one for The Donald

Donald Trump (to Hugh Hewitt, Aug 26, 2021):

“So I set up a conversation with him [Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar], and people said oh, you shouldn't be talking. Well, I set up a conversation with Kim Jong Un of North Korea. We didn't have a nuclear war. Had I not, then Obama would have been right. We would have had a nuclear war. President Obama said to me we're going to have a nuclear war with North Korea. I said have you ever spoken to him. He said no. And I said don't you think that might be a good idea. But anyway, I know he wanted to speak to him, but he never got to speak to him, and I think the other side didn't want to talk to Obama. So what happened is I spoke to the head of the, the known head, because it's [Baradar?] "Yeah, but I spoke to, and sort of the known head, but nobody was sure, but now I'm sure, and I was sure then when I was speaking to him. And I knew as soon as I spoke to him. And even the introduction, I say hello, and he screamed something very tough. And I then started with him. I said, listen, before we start the longtime conversation and conversations that we're going to have, I have to say one thing, and I'll never have to say it again to you. And here's what I say. If you do anything bad to the United States of America, if you do anything bad to any of our civilians, to any American citizen, or if you do anything out of the normal, you know, they've been fighting for a thousand years, but out of the normal, because you've had your wars, and if you do anything out of the normal, but anything bad to America or any American citizens, I will hit you harder than anybody has ever been hit in world history. You will be hit harder than any country and any person has ever been hit in world history. And we will start with the exact location and the exact town, and it's right here. And I believe I repeated the name of his town. That will be the first place that we start. And I won't be able to speak to you anymore after that, and isn't that a very sad thing? But that is the story. And then he asked me one question, and I'd rather not repeat that question, because it's a very scary question. But he asked me one question, and I gave him the answer yes. And then after it was all done, I said OK, now I've said what I'm going to say. Let's have a conversation. And I said we're going to be leaving after 21 years. And when we leave, you're going to leave us alone, and we're going to leave with great dignity and great honor. And we are going to take care of this situation. We're going to take our time. We had a date of May 1, but they missed a couple of conditions. We had some very strong conditions, Hugh. But they missed a couple of conditions. I wanted to be out by May 1. I had spoken to him quite a bit before May 1, but we had a condition of May 1. But they missed conditions, and so therefore, I bombed and we hit them very hard. And then we said we will agree to those conditions. I said no, you've already agreed to them. Don't play games. We had them so good. They weren't in Kabul. You take a look at when they started taking over Afghanistan. It's when I left. When I left, that's when it started, they started going wild, because they were dealing with another president. And I never realized, and of course I realized the importance and power of the presidency, but I never realized how important the office of the president is until this happened, because when I watched what happened over the last week and a half with some horrible, stupid decisions that were made, number one being allowing our military to leave before the civilians and before we get all of our equipment back, $83 billion dollars. And not, nobody can even comprehend that much equipment. Thousands of vehicles, thousands, you saw the list of vehicles.”

|

| Cullman AL Aug 2021 MAGA rally |

|

| Click to enlarge. |

Apparently Trump doesn't remember all the times he talked about negotiating with the 'smart,' 'sharp' Taliban pic.twitter.com/fGMe6vFLRw

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) August 28, 2021

Wednesday, August 25, 2021

"Ladies and gentlemen, we have a completely full flight tonight."

PROLOGUE

ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE

September 1996

IN THE TATTERED, cargo-strewn cabin of an Ariana Afghan Airlines passenger jet streaking above Punjab toward Kabul sat a stocky, broadfaced American with short graying hair. He was a friendly man in his early fifties who spoke in a flat midwestern accent. He looked as if he might be a dentist, an acquaintance once remarked. Gary Schroen had served for twenty-six years as an officer in the Central Intelligence Agency’s clandestine services. He was now, in September 1996, chief of station in Islamabad, Pakistan. He spoke Persian and its cousin, Dari, one of Afghanistan’s two main languages. In spy terminology, Schroen was an operator. He recruited and managed paid intelligence agents, conducted espionage operations, and supervised covert actions against foreign governments and terrorist groups. A few weeks before, with approval from CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, he had made contact through intermediaries with Ahmed Shah Massoud, the celebrated anti-Soviet guerrilla commander, now defense minister in a war-battered Afghan government crumbling from within. Schroen had requested a meeting, and Massoud had accepted.

They had not spoken in five years. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, as allies battling Soviet occupation forces and their Afghan communist proxies, the CIA had pumped cash stipends as high as $200,000 a month to Massoud and his Islamic guerrilla organization, along with weapons and other supplies. Between 1989 and 1991, Schroen had personally delivered some of the cash. But the aid stopped in December 1991 when the Soviet Union dissolved. The United States government decided it had no further interests in Afghanistan.

Meanwhile the country had collapsed. Kabul, once an elegant city of broad streets and walled gardens tucked spectacularly amid barren crags, had been pummelled by its warlords into a state of physical ruin and human misery that compared unfavorably to the very worst places on Earth. Armed factions within armed factions erupted seasonally in vicious urban battles, blasting down mud-brick block after mud-brick block in search of tactical advantages usually apparent only to them. Militias led by Islamic scholars who disagreed profoundly over religious minutia baked prisoners of war to death by the hundreds in discarded metal shipping containers. The city had been without electricity since 1993. Hundreds of thousands of Kabulis relied for daily bread and tea on the courageous but limited efforts of international charities. In some sections of the countryside thousands of displaced refugees died of malnutrition and preventable disease because they could not reach clinics and feeding stations. And all the while neighboring countries—Pakistan, Iran, India, Saudi Arabia—delivered pallets of guns and money to their preferred Afghan proxies. The governments of these countries sought territorial advantage over their neighbors. Money and weapons also arrived from individuals or Islamic charities seeking to extend their spiritual and political influence by proselytizing to the destitute.

Ahmed Shah Massoud remained Afghanistan’s most formidable military leader. A sinewy man with a wispy beard and penetrating dark eyes, he had become a charismatic popular leader, especially in northeastern Afghanistan. There he had fought and negotiated with equal imagination during the 1980s, punishing and frustrating Soviet generals. Massoud saw politics and war as intertwined. He was an attentive student of Mao and other successful guerrilla leaders. Some wondered as time passed if he could imagine a life without guerrilla conflict. Yet through various councils and coalitions, he had also proven able to acquire power by sharing it. During the long horror of the Soviet occupation, Massoud had symbolized for many Afghans—especially his own Tajik people—the spirit and potential of their brave resistance. He was above all an independent man. He surrounded himself with books. He prayed piously, read Persian poetry, studied Islamic theology, and immersed himself in the history of guerrilla warfare. He was drawn to the doctrines of revolutionary and political Islam, but he had also established himself as a broadminded, tolerant Afghan nationalist.

That September 1996, however, Massoud’s reputation had fallen to a low ebb. His passage from rebellion during the 1980s to governance in the 1990s had evolved disastrously. After the collapse of Afghan communism he had joined Kabul’s newly triumphant but unsettled Islamic coalition as its defense minister. Attacked by rivals armed in Pakistan, Massoud counterattacked, and as he did, he became the bloodstained power behind a failed, self-immolating government. His allies to the north smuggled heroin. He was unable to unify or pacify the country. His troops showed poor discipline. Some of them mercilessly massacred rivals while battling for control of Kabul neighborhoods.

Promising to cleanse the nation of its warlords, including Massoud, a new militia movement swept from Afghanistan’s south beginning in 1994. Its turbaned, eye-shadowed leaders declared that the Koran would slay the Lion of Panjshir, as Massoud was known, where other means had failed. They traveled behind white banners raised in the name of an unusually severe school of Islam that promoted lengthy and bizarre rules of personal conduct. These Taliban, or students, as they called themselves, now controlled vast areas of southern and western Afghanistan. Their rising strength shook Massoud. The Taliban traveled in shiny new Toyota double-cab pickup trucks. They carried fresh weapons and ample ammunition. Mysteriously, they repaired and flew former Soviet fighter aircraft, despite only rudimentary military experience among their leaders…

Coll, Steve (2004-12-27T22:58:59). Ghost Wars. Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

AFTERWORD

…Overall, I feel very fortunate that the documents and testimony obtained by the 9/11 Commission confirmed rather than contradicted my original narrative. In the end a journalist is only as good as his sources, and now that the commission has laid bare such a full record, I am more grateful than ever for the honesty, balance, and precision displayed by my most important sources during my original research. Still, there are a few significant chronological errors in the third part of the first edition. Some involve the exact timing of the several cases where President Clinton and his national security cabinet secretly considered firing cruise missiles at Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan. The commission’s investigation shows that the last of these episodes occurred in the spring of 1999, not the autumn of 2000, as I had originally reported, relying on a published interview with Clinton for the date. The commission’s work also makes clear that some of my sources, in talking to me about these incidents, occasionally conflated or combined in their memories episodes that had occurred separately. Beyond the intrinsic benefits of precision, these discrepancies are probably significant mainly because, now untangled, they locate specifically the political moments in which Clinton made his crucial decisions in his secret campaign against bin Laden—in one episode, for instance, the president had to decide whether to fire cruise missiles in the same week that he faced an impeachment trial in the U.S. Senate. The commission’s efforts still leave a few small mysteries in the record. For instance, it is still not clear to me when the Pakistani government first proposed collaborating with the CIA to train a commando team to try to capture or kill bin Laden—in December of 1998, as my interview sources place it, or the following summer, when the training clearly began in earnest. On these and other chronology issues I have made adjustments in the main text and clarified sourcing in the notes… [p. 577]

Q: What's roughly 40 times the size of Afghanistan's GDP?A: The annual U.S. Defense Department budget.

SOVIET FOREIGN MINISTER Eduard Shevardnadze briefed the inner Politburo group in May about Najibullah’s early efforts to pursue a new policy of “national reconciliation” that might outflank the CIA-backed rebels. The program was producing “a certain result, but very modest.”A doozy, that.

They were all frustrated with Afghanistan. How could you have a policy of national reconciliation without a nation? There was no sense of homeland in Afghanistan, they complained, nothing like the feeling they had for Russia.

“This needs to be remembered: There can be no Afghanistan without Islam,” Gorbachev said. “ There’s nothing to replace it with now. But if the name of the party is kept, then the word ‘Islamic’ needs to be included in it. Afghanistan needs to be returned to a condition which is natural for it. The mujahedin need to be more aggressively invited into power at the grassroots.”

The Americans were a large obstacle, they agreed. Surely they would align themselves with a Soviet decision to withdraw—if they knew it was serious. And the superpowers would have certain goals in common: a desire for stability in the Central Asian region and a desire to contain Islamic fundamentalism. “ We have not approached the United States of America in a real way,” Gorbachev said. “ They need to be associated with the political solution, to be invited. This is the correct policy. There’s an opportunity here.”

In Washington the following September, Shevardnadze used the personal trust that had developed between him and Secretary of State George Shultz to disclose for the first time the decision taken in the Politburo the previous autumn. Their staffs were in a working session on regional disputes when Shevardnadze called Shultz aside privately. The Georgian opened with a quiet directness, Shultz recalled. “ We will leave Afghanistan,” Shevardnadze said. “It may be in five months or a year, but it is not a question of it happening in the remote future.” He chose his words so that Shultz would understand their gravity. “I say with all responsibility that a political decision to leave has been made.”

Shultz was so struck by the significance of the news that it half-panicked him. He feared that if he told the right-wingers in Reagan’s Cabinet what Shevardnadze had said, and endorsed the disclosure as sincere, he would be accused of going soft on Moscow. He kept the conversation to himself for weeks.

Shevardnadze had asked for American cooperation in limiting the spread of “Islamic fundamentalism.” Shultz was sympathetic, but no high-level Reagan administration officials ever gave much thought to the issue. They never considered pressing Pakistani intelligence to begin shifting support away from the Muslim Brotherhood–connected factions and toward more friendly Afghan leadership, whether for the Soviets’ sake or America’s. The CIA and others in Washington discounted warnings from Soviet leadership about Islamic radicalism. The warnings were just a way to deflect attention from Soviet failings, American hard-liners decided.

Yet even in private the Soviets worried about Islamic radicalism encroaching on their southern rim, and they knew that once they withdrew from Afghanistan, their own border would mark the next frontier for the more ambitious jihadists. Still, their public denunciations of Hekmatyar and other Islamists remained wooden, awkward, hyperbolic, and easy to dismiss.

Gorbachev was moving faster now than the CIA could fully absorb.

On December 4, 1987, in a fancy Washington, D.C., bistro called Maison Blanche, Robert Gates, now the acting CIA director, sat down for dinner with his KGB counterpart, Vladimir Kryuchkov, chief of the Soviet spy agency. It was an unprecedented session. They talked about the entire gamut of U.S.-Soviet relations. Kryuchkov was running a productive agent inside the CIA at the time, Aldrich Ames, which may have contributed to a certain smugness perceived by Gates.

On Afghanistan, Kryuchkov assured Gates that the Soviet Union now wanted to get out but needed CIA cooperation to find a political solution. He and other Soviet leaders were fearful about the rise to power in Afghanistan of another fundamentalist Islamic government, a Sunni complement to Shiite Iran. “You seem fully occupied in trying to deal with just one fundamentalist Islamic state,” Kryuchkov told Gates.

Gorbachev hoped that in exchange for a Soviet withdrawal he could persuade the CIA to cut off aid to its Afghan rebels. Reagan told him in a summit meeting five days later that this was impossible. The next day Gorbachev tried his luck with Vice President George Bush. “If we were to begin to withdraw troops while American aid continued, then this would lead to a bloody war in the country,” Gorbachev pleaded.

Bush consoled him: “ We are not in favor of installing an exclusively pro-American regime in Afghanistan. This is not U.S. policy.”

There was no American policy on Afghan politics at the time, only the de facto promotion of Pakistani goals as carried out by Pakistani intelligence. The CIA forecasted repeatedly during this period that postwar Afghanistan was going to be an awful mess; nobody could prevent that. Let the Pakistanis sort out the regional politics. This was their neighborhood.

Gates joined Shultz, Michael Armacost, Morton Abramowitz, and Deputy Secretary of State John Whitehead for a lighthearted luncheon on New Year’s Eve. They joked their way through a serious debate about whether Shevardnadze meant what he said when he had told Shultz in September that they were getting out. At the table only Gates—reflecting the views of many of his colleagues at the CIA—argued that it would not happen, that no Soviet withdrawal was likely, that Moscow was engaged in a political deception.

The CIA director bet Armacost $25 that the Soviets would not be out of Afghanistan before the end of the Reagan administration. A few months later he paid Armacost the money. [Coll, pp. 167-169]

War with noble purpose

“Afghanistan is being, if anything, bombed OUT of the Stone Age,” quipped Christopher Hitchens. A brutal Taliban regime was ending. Women were going to school. Men were shaving their beards and looking, in wonder, at their naked faces in the mirror. No wonder Iraq, suffering under the boot of a truly evil dictator, began to look inviting.

A buddy of mine, the journalist and veteran Jacob Siegel, recently admitted to having an instinctive recoil against men our age who didn’t serve in the military. “It’s unfair, but I feel that,” he said. “Who excused you, you know? Or another way of putting that would be, Why did you think you had a choice? I know it’s a volunteer army but, the volunteer army is a trick question, you know? You’re supposed to say yes if you have any honor.”

More of us veterans feel that than we publicly admit. The voice in our heads whispering, If you had honor, you joined. You went to make the world safe. To plant peace in long-suffering nations, with no selfish ends to serve, desiring no conquest, no dominion. We were told that we were the champions of the rights of mankind.

The next time that feeling comes around, remember what it wrought. 9/11 unified America. It overcame partisan divides, bound us together, and gave us the sense of common purpose so lacking in today’s poisonous politics. And nothing that we have done as a nation since has been so catastrophically destructive as what we did when we were enraptured by the warm glow of victimization and felt like we could do anything, together.

Tuesday, August 24, 2021

"Fascism or Communism? Which one is it?"

Sunday, August 22, 2021

Sometimes a SIGAR is just a SIGAR

For a decade, I had been working to combat corruption. I’d analyzed it in countries like Nigeria and Afghanistan—where I had lived for years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

I had set up a small manufacturing cooperative in downtown Kandahar: Taliban country. We were women and men working together—a minor revolution. We were nine different tribes and ethnic groups, ten if you count me, in twenty people. With improvised bombs detonating sometimes every day, we bought apricot kernels in bulk and pressed wild pistachios and distilled essential oils and laughed our heads off as we mixed and kneaded and polished soaps to look like river-worn cobbles and concocted fragrant lotions, and talked politics all day long. And I discovered something I could never have imagined. Religious fanaticism, these men and women told me, was not driving their friends and cousins into the arms of the extremist Taliban. Indignation at their government’s corruption was—and at Americans’ role in enabling it.

It was a remarkable idea. I asked around, trying it out on other Afghans, trying to understand the structure of what I soon could see was a system. I went to work for the U.S. military leadership: serving two commanders of the international forces in Kabul, then the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon. I helped launch the first anticorruption efforts the United States undertook. In 2010, in response to an almost comically ambivalent plan put forth by the State Department, Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Admiral Mike Mullen—my boss—persuaded his colleagues that it was time, in his words, “to get serious.” He put me in charge of redrafting the plan. He passed the result to the deputy national security advisor for Iraq and Afghanistan, Douglas Lute.

And there it sat.

Chayes, Sarah. On Corruption in America (pp. 5-6). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Monday, August 16, 2021

Afghanistan

"The US launched the Afghan war 20 years ago in a mood of vengeance, resolve and unity, after al Qaeda's attacks on New York and Washington shattered the post-Cold War myth of American hyper power. It is ending it in a rushed race to get out, humbled by a primitive militia, that is nevertheless ready to die for jihad on its home soil and is re-imposing its feudal writ on a war-ravaged nation that bleeds foreign invaders dry." —CNNUPDATE: "Raise your hand if you want to see these people coming to your town." —Newsmax host & former Trump advisor Steve Cortes."This plane should have been full of Americans. America first!" —Donald Trump

Saturday, August 14, 2021

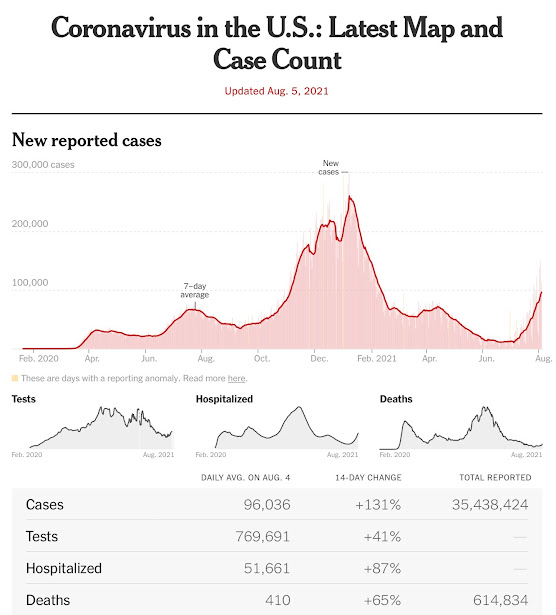

The COVID19 Hoax Plandemic

At a Board of County Commissioners Meeting in Kansas:

— Leah McElrath 🏳️🌈 (@leahmcelrath) August 13, 2021

A woman starts with, “There is zero evidence COVID-19 exists in the world,” claims vaccines are a “bio-weapon,” talks about child trafficking, and ends with “Trump won.”

This is a cult. A death cult.pic.twitter.com/KVoSFvjJ49

The Evolutionary Psychology of Conflict and the Functions of Falsehood (2020)

Abstract

Truth is commonly viewed as the first casualty of war. As such the current circulation of fake news, conspiracy theories and other hostile political rumors is not a unique phenomenon but merely another example of how people are motivated to dispend with truth in situations of conflict. In this chapter, we theorize about the potentially evolved roots of this motivation and outline the structure of the underlying psychology. Specifically, we focus on how the occurrence of intergroup conflict throughout human evolutionary history has built psychological motivations into the human mind to spread information that (a) mobilize the ingroup against the outgroup, (b) facilitate the coordination of attention within the group and (c) signal commitment to the group to fellow ingroup members. In all these instances, we argue, human psychology is designed to select information that accomplishes these goals most efficiently rather than to select information on the basis of its veracity. Accordingly, we hypothesize that humans in specific instances are psychologically prepared to prioritize misinformation over truth.

Abstract

Reasoning is generally seen as a means to improve knowledge and make better decisions. However, much evidence shows that reasoning often leads to epistemic distortions and poor decisions. This suggests that the function of reasoning should be rethought. Our hypothesis is that the function of reasoning is argumentative. It is to devise and evaluate arguments intended to persuade. Reasoning so conceived is adaptive given the exceptional dependence of humans on communication and their vulnerability to misinformation. A wide range of evidence in the psychology of reasoning and decision making can be reinterpreted and better explained in the light of this hypothesis. Poor performance in standard reasoning tasks is explained by the lack of argumentative context. When the same problems are placed in a proper argumentative setting, people turn out to be skilled arguers. Skilled arguers, however, are not after the truth but after arguments supporting their views. This explains the notorious confirmation bias. This bias is apparent not only when people are actually arguing, but also when they are reasoning proactively from the perspective of having to defend their opinions. Reasoning so motivated can distort evaluations and attitudes and allow erroneous beliefs to persist. Proactively used reasoning also favors decisions that are easy to justify but not necessarily better. In all these instances traditionally described as failures or flaws, reasoning does exactly what can be expected of an argumentative device: Look for arguments that support a given conclusion, and, ceteris paribus, favor conclusions for which arguments can be found.

Friday, August 13, 2021

Happy #ReinstatementDay

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

The IPCC 2021 Report

Friday, August 6, 2021

Theranos: Elizabeth Holmes' accountability, finally?

Monday, August 2, 2021

RSV: Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Something very strange has been happening in Missouri: A hospital in the state, Ozarks Healthcare, had to create a “private setting” for patients afraid of being seen getting vaccinated against COVID-19. In a video produced by the hospital, the physician Priscilla Frase says, “Several people come in to get vaccinated who have tried to sort of disguise their appearance and even went so far as to say, ‘Please, please, please don’t let anybody know that I got this vaccine.’” Although they want to protect themselves from the coronavirus and its variants, these patients are desperate to ensure that their vaccine-skeptical friends and family never find out what they have done.