A scholar's debut book way worthy of your time and close attention.

The Amazon recommendation for this new release hit my inbox early in the week. I bit forthwith, after reading the sample. Happy that I did so.

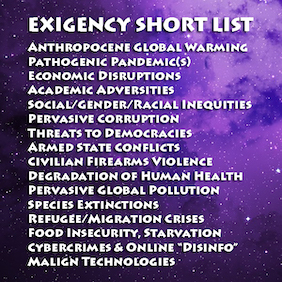

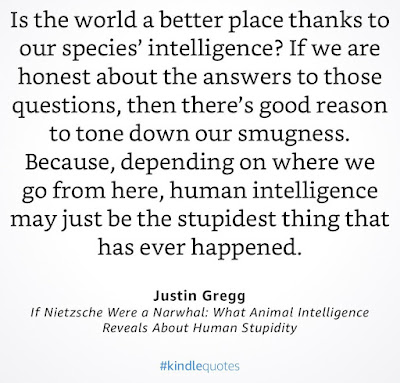

Goes to my abiding Jones for information going to our persistent, worrisome (IMO), and worsening Exigent Priorities and the potentially mitigative / beneficent applicable role of so-called "Deliberation Science." (My cranky "so-called" scare quotes caveat is starting to ebb, but myriad salient questions remain.)

I like to let authors speak for themselves (they certainly know more than do I), so let us cut to the chase (final chapter):

CHAPTER 8

CONNECT

How Two Brains Get on the Same Wavelength

In the book Talking to Strangers, Malcolm Gladwell takes his readers through a series of dramatic, real-world examples of misunderstandings between people that make two points very clearly: (1) Understanding other people can be really difficult; and (2) misunderstandings between people can have disastrous consequences. From Ponzi schemes to genocide, when we get it wrong—we really get it wrong. Is it any wonder that some of us are hesitant to explore relationships with others?

In this book, I’ve provided the background knowledge to help you understand the biological barrier that can drive misalignment between people. When two different brains, shaped by the confluence of their unique biology and life experiences, interact with each other in a shared environment, they do so through the barrier of the different subjective realities that they create.

Yet the very brains that make it difficult to see eye to eye with someone else are the same ones that inspire us to try. And though it’s certainly truer for some more than others, our social human brains crave connection. From early caregiving relationships through the different types of intimate adult partnerships we form, our brains contain a host of built-in mechanisms that drive us to connect. And this makes good sense, given how central relationships are to our survival. In fact, forming connections with others is one of the most important brain functions of all.

I think George R. R. Martin got to the heart of this when he wrote, “When the snow falls and the white winds blow, the lone wolf dies but the pack survives”—as a central part of the House Stark narrative in Game of Thrones. Because when times get tough, having close relationships is critical to our survival, even if most humans no longer rely directly on one another for things like warmth or hunting in packs. We have seen this play out over and over in health-related research, where the power of touch has been shown to help the brains and bodies of premature babies develop, and social support networks help buffer the health effects of chronic illnesses like AIDS. To put the importance of close relationships into a more concrete, health-related context, consider the results of a recent meta-analysis conducted by Julianne Holt-Lunstad and Timothy Smith. After analyzing data collected from more than 300,000 participants around the world, the authors concluded that lacking close interpersonal relationships was more than twice as strongly associated with early mortality as either excessive drinking or obesity.

And I’m sure that our understanding of the health risks associated with loneliness will increase exponentially as psychologists and healthcare professionals start to crunch the data collected from the massive “social isolation experiment” that the COVID-19 pandemic created. A quick search through the scientific literature using keywords “social isolation,” “pandemic,” and “health” returned more than 1,500 articles published in the last two years on this topic. Though I can’t quite get to the place of calling this a silver lining, each of these studies will contribute to our understanding of why interpersonal connection is a necessary component of healthy living, and which of the many ingredients of successful connections promote physical and mental health. But will they provide the recipe for forming healthy relationships?…

Prat, Chantel. The Neuroscience of You (pp. 287-289). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition

Reflecting to an earlier posting:

Excellent. Not kidding.

WHEN YOU THINK ABOUT the individual genetic and developmental differences that impact the sensory portions of our nervous systems, it’s remarkable that we can agree on a shared reality at all…We have a new winner in the "Best Place to Hide a $100 Bill From Donald Trump" awards.

…Each of us operates from a different perception of the world and a different perception of ourselves.

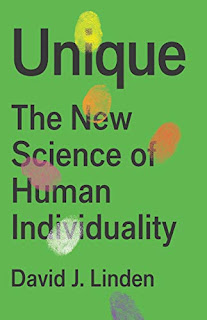

A portion of the individual variation in sensory systems is innate. But those innate effects are elaborated and magnified with time as we accumulate experiences, expectations, and memories, filtered through and in turn modifying those very same sensory systems. In this way, the interacting forces of heredity, experience, plasticity, and development resonate to make us unique.

Linden, David. Unique (pp. 253-254). Basic Books. Kindle Edition.

How we become unique is one of the deepest questions that we can ask. The answers, where they exist, have profound implications, and not just for internet dating. They inform how we think about morality, public policy, faith, health care, education, and the law. For example: If a behavioral trait like aggression has a heritable component, then are people born with a biological predisposition toward it less legally culpable for their violent acts? Another question: If we know that poverty reduces the heritability of a valued human trait like height, should we, as a society, seek to reduce the inequities that impede people from fulfilling their genetic capacity? These are the types of questions where the science of human individuality can inform discussion.I sorely want David to defy the odds and survive. Read his book and you will agree.

Although investigating the origins of individuality is not just an endeavor for biologists—cultural anthropologists, artists, historians, linguists, literary theorists, philosophers, psychologists, and many others have a seat at this table—many of this topic’s most important aspects involve fundamental questions about the development, genetics, and plasticity of the nervous system. The good news is that recent scientific findings are illuminating this question in ways that are exciting and sometimes counterintuitive. The better news is that it doesn’t just boil down to the same tiresome nature-versus-nurture debate that has been impeding progress and boring people for years. Genes are built to be modified by experience. That experience is not just the obvious stuff, like how your parents raised you, but more complicated and fascinating things like the diseases you’ve had (or those that your mother had while she was carrying you in utero), the foods you’ve eaten, the bacteria that reside in your body, the weather during your early development, and the long reach of culture and technology.

So, let’s dig into the science. It can be controversial stuff. Questions about the origins of human individuality speak directly to who we are. They challenge our concepts of nation, gender, and race. They are inherently political and incite strong passions. For over 150 years, from the high colonial era to the present, these arguments have separated the political Right from the Left more clearly than any issue of policy.

Given this fraught backdrop, I’ll do my best to play it straight and synthesize the current scientific consensus (where it exists), explain the debates, and point out where the sidewalk of our understanding simply ends… [pp 6-7]

"WHEN

YOU THINK ABOUT the individual genetic and developmental differences

that impact the sensory portions of our nervous systems, it’s remarkable

that we can agree on a shared reality at all."

Yeah. I am reminded of some David Eagleman.

…If you’ve ever doubted the significance of brain plasticity, rest assured that its tendrils reach from the individual to the society.

Because of livewiring, we are each a vessel of space and time. We drop into a particular spot on the world and vacuum in the details of that spot. We become, in essence, a recording device for our moment in the world.

When you meet an older person and feel shocked by the opinions or worldview she holds, you can try to empathize with her as a recording device for her window of time and her set of experiences. Someday your brain will be that time-ossified snapshot that frustrates the next generation.

Here’s a nugget from my vessel: I remember a song produced in 1985 called “We Are the World.” Dozens of superstar musicians performed it to raise money for impoverished children in Africa. The theme was that each of us shares responsibility for the well-being of everyone. Looking back on the song now, I can’t help but see another interpretation through my lens as a neuroscientist. We generally go through life thinking there’s me and there’s the world. But as we’ve seen in this book, who you are emerges from everything you’ve interacted with: your environment, all of your experiences, your friends, your enemies, your culture, your belief system, your era—all of it. Although we value statements such as “he’s his own man” or “she’s an independent thinker,” there is in fact no way to separate yourself from the rich context in which you’re embedded. There is no you without the external. Your beliefs and dogmas and aspirations are shaped by it, inside and out, like a sculpture from a block of marble. Thanks to livewiring, each of us is the world.

Eagleman, David. Livewired (pp. 244-245). Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

PRIOR POST ON SOME TOPICAL ERRATA

'eh?

Some things that bedevil our thinking, particularly as it goes to persuasion and influence:

There is no first-person singular present-tense active voice usage of the word "wrong." No one ever says "I AM wrong."

[props to Kathryn Schulz]

Our aggregate default is that we're right about everything. To the

extent that we continue to survive, that's an understandable

assumption—as it pertains to minor, inconsequential issues, anyway, and

it inexorably tilts us toward "confirmation bias."

Our education system mostly tells us there's one "right answer" to every question—lurking amid a boatload of "wrong ones."

And, those who quickly alight on the "right answer" get reinforced and nurtured as they move through the system.

Being wrong is not a synonym for being "stupid" or ignorant.

Neither is "ignorant" a synonym for "stupid." But it's mostly epithetically spun that way; i.e., that you "ignore reality."

Humans "reason" to WIN the argument.

Should truth happen along the way, so much the better. (See "Why Do Humans Reason?" by Sperber & Mercier) Evolutionary adaptive utility, "The Pen is Mightier Than The Sword."

He/She with the best story WINS!

Trial Lawyering 101. Prior to writing and movable type, stories were the whole ballgame. Hence, our evolved affinity.

Once you decide that X is right or wrong / good or bad, you cannot unring that bell.

A staple look-before-you-leap admonishment of mine back when I was teaching "Critical Thinking."

If,

when it's all said and done, your logic is impeccable, and your facts

and evidence are bulletproof, yet you remain unpersuasive, what have you

really accomplished?''

Another

classroom staple of mine. That one was "exceeding my brief" as it were,

but my Sups never noticed or cared. Anyway, my overall

teach-to-the-text priority focus as a piddly Adjunct necessarily had to

be "OK, here's how this stuff works. Take it or leave it."

Another random observation. Even though I've taught collegiate "Critical Thinking," I've never much liked the phrase. Many students routinely came into my classes eager to be "critical" in the sense of being "contentious," "argumentative"—ready to throw down over their pet peeves and argue about stuff, "get shit off their chests." Sound familiar these days?

____

BACK TO ZOE

Way more to come. Gotta turn in.

UPDATE. MORE DR. PRAT

…every single life experience changes your brain. Some of the changes are inconsequential and others are incremental. But on rare occasions, for better or for worse, a single event can change the way we work, forever.Yeah, that squares nicely with the views of other neuroscience SMEs.

This is an important note to take, before diving deeper into the neuroscience of you. The fact that something about your brain causes you to think, feel, or behave in a certain way does not necessarily mean either that you were born that way or that it can’t change. The truth is that your brain is a moving target. And most research linking brains to behaviors, like my work on the two hemispheres and reading skill, only looks at a single point in time—a snapshot, so to speak. With this kind of experiment, it’s simply impossible to tell how much of a particular brain design is stable or has been shaped by your experiences. [The Neuroscience of You, p. 25]

APROPOS OF "DELIBERATION SCIENCE & DEMOCRACY," A BRIEF ASIDE

If you've not read Marilynne Robinson, do yourselves a serious favor. She rocks. (Delightfully, Alan Jacobs cited her in "How to Think." I'd already read her. Humblingly eloquent, bracingly scary smart.)

Uh, hel-LO?

"The only person who enjoys change is a baby with a wet diaper."

—Brent James, MD, M.Stat (a mentor)

—Brent James, MD, M.Stat (a mentor)

More shortly. Into the single malt Scotch at the moment...

____

SOME TOPICAL ELEMENTS OF DELIBERATION SCIENCE?Not in any particular order here, nor mutually exclusive. And, what am I overlooking?

- Deductive logic (incl. Boolean logic?)

- Inductive inference

- Abductive inference

- Fuzzy logic

- Argument analysis and evaluation

- Philosophy of science

- Statistics

- Data science

- Game theory

- Rhetoric

- Linguistics (incl. semantics, pragmatics, semiotics, "Corpus Linguistics")

- Psychology (developmental, cognitive, social...)

- Sociology

- Cultural anthropology

- Political science

- History and systems of jurisprudence

- Moral philosophy and ethics

- Neuroscience

Behaviorlal Genetics?

MORE DR. CHANTEL

…From the mundane activities, like estimating the angle your bike can turn at a given speed to the more profound decision points in life, like figuring out whether a particular choice will bring you more joy or more pain, your brain spends every waking moment engaged in elaborate problem-solving and decision-making algorithms. And of course, each brain goes about it a bit differently…Yeah. All of which bear on "deliberation." Ja?

…In fact, every lived experience physically changes your brain, resulting in a brain that is fine-tuned for operating in the environments that shaped it. And I think you might be surprised to learn what counts as an experience from your brain’s perspective. Ultimately, these experiences fundamentally shape the way we see the world we inhabit as well as how we understand people and situations that we don’t have a lot of experience with. [The Neuroscience of You [pp. 154-155]

"Deliberate" (adjective): intentional;"Deliberate" (verb): to consider carefully, factually, rationally;"Deliberation" (noun): the process of considering carefully, factually, rationally.

You encounter the word "deliberation." What typically first comes to mind, reflexively?

We can learn a ton from that.

My son recently did jury service.

OK, after "jury deliberations," what might we think of? "Supreme Court deliberations?" "Congressional deliberations?" (Skeptics might argue the latter to be a contradiction in terms.)

"Considering carefully." What constitutes adequate, consistent "care?"

FROM THE WIKI

Deliberation is a process of thoughtfully weighing options, usually prior to voting. Deliberation emphasizes the use of logic and reason as opposed to power-struggle, creativity, or dialogue. Group decisions are generally made after deliberation through a vote or consensus of those involved.Nicely stated.

In legal settings a jury famously uses deliberation because it is given specific options, like guilty or not guilty, along with information and arguments to evaluate. In "deliberative democracy", the aim is for both elected officials and the general public to use deliberation rather than power-struggle as the basis for their vote…

In political philosophy, there is a wide range of views regarding how deliberation becomes a possibility within particular governmental regimes. Most recently, the uptake of deliberation by political philosophy embraces it alternatively as a crucial component or the death-knell of democratic systems. Much of contemporary democratic theory juxtaposes an optimism about democracy against excessively hegemonic, fascist, or otherwise authoritarian regimes. Thus, the position of deliberation is highly contested and is defined variously by different camps within contemporary political philosophy. In its most general (and therefore, most ambiguous) sense, deliberation describes a process of interaction between various subjects/subjectivities dictated by a particular set of norms, rules, or fixed boundaries. Deliberative ideals often include "face-to-face discussion, the implementation of good public policy, decisionmaking competence, and critical mass."

The origins of philosophical interest in deliberation can be traced to Aristotle’s concept of phronesis, understood as "prudence" or "practical wisdom" and its exercise by individuals who deliberate in order to discern the positive or negative consequences of potential actions…

Digression. Of relevance? a 2017 post of mine.

|

| Click |

UPDATE

Another good Chantel Prat interview, at CUNY's Open Mind.

Yeah, it's all good.

QUICK DIGRESSION

Annie Duke's new book is out.

Relevant to the topic here.

We view grit and quit as opposing forces. After all, you either persevere or you abandon course. You can’t do both at the same time, and in the battle between the two, quitting has clearly lost.What's the joke? "Rehab is for quitters."

While grit is a virtue, quitting is a vice.

The advice of legendarily successful people is often boiled down to the same message: Stick to things and you will succeed. As Thomas Edison said, “Our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time.” Soccer legend Abby Wambach echoed this sentiment over a century later when she said, “You must not only have competitiveness but ability, regardless of the circumstance you face, to never quit.”

Similar inspirational advice is attributed to other great sports champions and coaches, such as Babe Ruth, Vince Lombardi, Bear Bryant, Jack Nicklaus, Mike Ditka, Walter Payton, Joe Montana, and Billie Jean King. You can also find almost identical quotes from other legendary business successes through the ages, from Conrad Hilton to Ted Turner to Richard Branson.

All these famous people, and countless others, have united behind variations of the expression “Quitters never win, and winners never quit.”

It is rare to find any popular quote in favor of quitting except one attributed to W. C. Fields: “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Then quit. There’s no use being a damn fool about it.”

Duke, Annie. Quit (p. xviii). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

UPDATE

More sources keep coming to mind. This is a 2008 release. Sounds like today.

CERTAINTY IS EVERYWHERE. FUNDAMENTALISM IS IN FULL bloom. Legions of authorities cloaked in total conviction tell us why we should invade country X, ban The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in schools, or eat stewed tomatoes; how much brain damage is necessary to justify a plea of diminished capacity; the precise moment when a sperm and an egg must be treated as a human being; and why the stock market will eventually revert to historical returns. A public change of mind is national news.But why? Is this simply a matter of stubbornness, arrogance, and/or misguided thinking, or is the problem more deeply rooted in brain biology? Since my early days in neurology training, I have been puzzled by this most basic of cognitive problems: What does it mean to be convinced? At first glance, this question might sound foolish. You study the evidence, weigh the pros and cons, and make a decision. If the evidence is strong enough, you are convinced that there is no other reasonable answer. Your resulting sense of certainty feels like the only logical and justifiable conclusion to a conscious and deliberate line of reasoning.But modern biology is pointing in a different direction. Consider for a moment an acutely delusional schizophrenic patient telling you with absolute certainty that three-legged Martians are secretly tapping his phone and monitoring his thoughts. The patient is utterly convinced of the “realness” of the Martians; he “knows” that they exist even if we can’t see them. And he is surprised that we aren’t convinced. Given what we now know about the biology of schizophrenia, we recognize that the patient’s brain chemistry has gone amok, resulting in wildly implausible thoughts that can’t be “talked away” with logic and contrary evidence. We accept that his false sense of conviction has arisen out of a disturbed neurochemistry.It is through extreme examples of brain malfunction that neurologists painstakingly explore how the brain works under normal circumstances. For example, most readers will be familiar with the case of Phineas Gage, the Vermont laborer whose skull and frontal region of the brain were pierced with an iron bar during an 1848 railroad construction accident.1 Miraculously, he lived, but with a dramatically altered personality. By gathering together information from family, friends, and employers, his physicians were able to piece together one of the earliest accurate descriptions of how the frontal lobe affects behavior...Burton, Robert Alan (2008-02-04T22:58:59.000). On Being Certain. St. Martin's Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

And: "Two Cheers For Uncertainty."

What?

[Oct 8th] Couple more relevant reads...

Fine young writer. Spot-on observations.

And, then, through David, I run into these peeps.

|

| Click |

The Center for Practical Wisdom was started by a group of scientists and scholars at the University of Chicago with an interest in human decision making that is concerned with how our decisions affect others. From Aristotle, our working definition of practical wisdom is practical decision making that leads to human flourishing. While much of the world, since Binet, the father of the IQ test, has focused on the importance of intelligence for society, intelligence is about solving problems without consideration for the impact of the solutions on others. By contrast, we think about practical wisdom or wise reasoning as considering value commitments that are concerned with understanding the impact of decisions on others.OK, cool. I'm kinda late to the party here. Will have to get up to speed on this.

More shortly.

__________

No comments:

Post a Comment