"But with all I don't know, you could fill up a library."

.

When I was in my 20s and writing my first book—I know, I really fucked up there—I came across a quote I can no longer find the source of that said, essentially, “You could fill a book with all I know, but with all I don’t know, you could fill a library.” It’s a helpful visualization, perhaps the most basic and pragmatic justification for deep reading. And though correlation is not causation, I submit that we’d save ourselves an enormous amount of trouble in the future if we’d agree to a simple litmus test: Immediately disregard anyone in the business of selling a vision who proudly proclaims they hate reading...

Tweeted him to tell him I'd be "stealin' it."

We have never before had access to so many perspectives, ideas, and information. Much of it is fleetingly interesting but ultimately inconsequential—not to be confused with expertise, let alone wisdom. This much is widely understood and discussed. The ease with which we can know things and communicate them to one another, as well as launder success in one realm into pseudo-authority in countless others, has combined with a traditional American tendency toward anti-intellectualism and celebrity worship. Toss in a decades-long decline in the humanities, and we get our superficial culture in which even the elite will openly disparage as pointless our main repositories for the very best that has been thought.Great article.

…In an ill-conceived profile from September, published on the Sequoia Capital website, the 30-year-old SBF rails against literature of any kind, lecturing a journalist on why he would “never” read a book. “I’m very skeptical of books,” he expands. “I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that. I think, if you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.”…

It is one thing in practice not to read books, or not to read them as much as one might wish. But it is something else entirely to despise the act in principle. Identifying as someone who categorically rejects books suggests a much larger deficiency of character …. receiving all of your information from the SBF ideal of six-paragraph blog posts, or from the movies and random conversations that Ye prefers, is as foolish as identifying as someone who chooses to eat only fast food.

Many books should not have been published, and writing one is an excruciating process full of failure. But when a book succeeds, even partially, it represents a level of concentration and refinement—a mastery of subject and style strengthened through patience and clarified in revision—that cannot be equaled. Writing a book is an extraordinarily disproportionate act: What can be consumed in a matter of hours takes years to bring to fruition. That is its virtue. And the rare patience a book still demands of a reader—those precious slow hours of deep focus—is also a virtue. One might reasonably ask just where, after all, these men have been in such a rush to get to? One might reasonably joke that the answer is either jail or obscurity…

"...when a book succeeds, even partially, it represents a level of concentration and refinement—a mastery of subject and style strengthened through patience and clarified in revision—that cannot be equaled. Writing a book is an extraordinarily disproportionate act: What can be consumed in a matter of hours takes years to bring to fruition. That is its virtue. And the rare patience a book still demands of a reader—those precious slow hours of deep focus—is also a virtue..."I continue to read for at least 30 hours a week, averaging 2-3 books a week plus all of my periodicals. There's just too much to learn and unlearn. 'Nuther fav quote of mine: "The best place to hide a $100 bill from Donald Trump is inside a book."

Just finished this one.

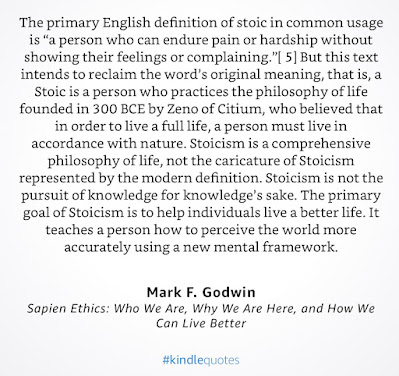

Stay tuned. Not yet sure about this one. It piqued my interest in light of my 1998 Master’s in Applied Ethics ("Ethics & Policy Studies") and my ongoing Jones for so-called "Deliberation Science."

Read this New Yorker article the other day. Led me to this book. Had to get it. Delightful thus far.

Early on, some "Taylorism 2.0" observations (I've taken my shots at Taylor across the years. I'm one of those humanistic progressive QI guys):

...Sometimes, digital enforcement happens through attempts to prevent violation, making rules more difficult to break—using code to make it more onerous (or even impossible) to deviate from an imposed rule. For example, digital rights management technology makes it (nearly) impossible to violate copyright law. If these technologies work as “perfectly” as intended, rule violation is completely impaired, and violation becomes practically impossible (or at least much more difficult). But even more common than tools of prevention are tools of detection—technologies that function not by making rule-violating behavior more difficult to execute, but by creating a comprehensive account of our behaviors. These are surveillance technologies. For example, body-worn cameras don’t make it impossible for a police officer to use unauthorized force against a civilian, but are intended to make the officer more accountable should they do so. These technologies may work by deterring sanctioned behaviors—knowing that one is being observed can incentivize rule-following—or because they enable enforcers to more swiftly detect and punish rule-breaking.

Perhaps nowhere do we see this trend more clearly than in the workplace, where surveillance over workers’ behaviors has become a favored method for compelling compliance with the aims of management. As we’ll see, this practice has deep roots—but contemporary workplace surveillance has some new features, too.

Work and the Future of Work

We often anticipate the “future of work” in either dreamy or dystopian terms. The phrase has been widely adopted by technologists and commentators, either to describe a paradisical ideal in which people have much greater autonomy and flexibility to do work in ways that suit them while affording them ample time for leisure; or, as a dark alternative, as a future in which workers have ever-diminishing social and economic power and in which their every move and thought is overseen, predicted, and optimized by management, human or algorithmic. Both visions, though, are united by the assumption that the future of work (whatever it looks like) will happen, well, in the future—that is to say, this is a vision of a time that is not now, and that is somehow different than now, or at least different enough that it deserves its own label.

It’s rather curious that we tend to talk in such future-oriented prognostications about what technological change will portend for work and the workplace. In other domains, the way we talk about technology tends to be more focused on what is occurring now or in the very near term; but when it comes to work, we maintain some temporal distance, at least in our discourse, from these changes. This is odd because the “future of work” is, of course, not some distant or discrete mode of social organization so unlike the one we have today. The management practices of tomorrow are, in many ways, not particularly different from the management practices of the past. They’re built on the same foundations—motivating efficiency, minimizing loss, optimizing processes, improving productivity. And one of the most common strategies for achieving these goals, then and now, is increased oversight over the activities of workers.

So what's new about today’s workplace surveillance? Is this not just more of the same, driven by the same organizational goals that have always motivated managerial oversight—even if the specific technologies that are used to do so have changed form in one way or another? Some workplace monitoring is old wine in a new bottle, a contemporary instantiation of the manager with a clipboard looming above the factory floor. This is not to say, of course, that these practices don’t deserve scrutiny or critique—but we should be precise about what, if anything, is new here.

In fact, there are some subtle but important dynamics that distinguish contemporary workplace surveillance from what’s come before, and that will become important in telling the truckers’ story. First, contemporary technologies facilitate surveillance in new kinds of workplaces. Geographically distributed and mobile workers, for example, have historically maintained more independence from oversight than workers centralized in nonmobile workplaces, like factories, call centers, and office buildings—but location tracking, sensor technology, and wireless networking have changed that. Porous boundaries between home and work also facilitate surveillance in new places. For example, the growth of work-from-home arrangements during the Covid-19 pandemic has led to greater use of tracking software to monitor workers’ keystrokes, locations, and web traffic—as well as video capture of the kitchen tables and living rooms in which their work now takes place.

New kinds of data also come to the fore. As sensor technologies become cheaper and easier to deploy, and workplace surveillance capability is more frequently embedded in software by default, employers are well positioned to capture more and more fine-grained data about workers’ movements and activities. Wearable technologies, like those used in Amazon’s warehouses, monitor and evaluate workers’ speed with much more precision than was previously possible—including the number and length of their bathroom breaks. Employers increasingly monitor and analyze datapoints like workers’ social media posts, phone calls, and attendance at meetings; Microsoft faced pushback in 2020 when it built “productivity scoring” into its widely used Office 365 product, which gave managers access to “73 pieces of granular data about worker behavior” like email and chat frequency. And as we’ll discuss, biometric data is also becoming more commonly collected in the workplace—from authentication mechanisms like fingerprint and retinal scans to behavioral data about workers’ attention and fatigue.

These new data streams fuel new kinds of analysis that impact how workers are managed. In some contexts, managerial decisions are implemented through opaque algorithmic systems that can create acute information asymmetries between workers and firms—like Uber’s use of algorithms to apportion rides and determine rates without making those rules transparent to its drivers. Other analyses are predictive, designed to forecast which workers are likely to be most productive, how many workers to staff at a given time to meet demand, or which worker is likely to make a sale to a particular customer.

Finally, contemporary workplace surveillance can blur boundaries between the workplace and other spheres of life, creating new kinds of entanglements across previously disparate domains. Surveillance of work-from-home environments can facilitate data collection about family, friends, and living situations. Managers often keep tabs on workers’ online activities on social media platforms. Workplace wellness programs can facilitate employers’ collection of data about worker health, stoking concerns about discrimination. And “bring-your-own-device” policies, in which an employer’s software is installed on a worker’s own personal phone or computer, can further muddle distinctions between home and work and create additional data privacy and security concerns.

Levy, Karen. Data Driven (pp. 6-9). Princeton University Press. Kindle Edition.

Scary smart. Law Degree and a Doctorate in Sociology from Princeton. What a Sheet (pdf).

Just guessing, based on her CV, she may be about 40 ( no personal bio info). But, I gotta say, were I a bartender and she came in, I'd be asking for ID.

Stay tuned...

__________

No comments:

Post a Comment