Theranos, FTX, and our long tradition of scams.

MORE NEWS & COMMENT

|

| From Naked Capitalism |

Hmmm... will SBF's father providing legal advice also conveniently serve as asserted "attorney-client privilege" cover?

FROM AN INTERESTING RECENT INTERVIEW WITH CORY DOCTOROW

In your next novel, “Red Team Blues,” you focus on Martin Hench, a sixty-seven-year-old forensic accountant, who is tasked with recovering a set of stolen signing keys that, with some technical finagling, can permit one to rewrite a blockchain’s distributed ledger, swiping assets from one side to the other, as it were. Do you think blockchain tech is less secure than enthusiasts portray it to be?

I think so. One of the things about pseudonymity is that it has a cumulative information-leakage problem. So, if you’re pseudonymous, and you make one transaction and then never do anything else, that transaction will likely be very hard to trace back to you, right? If you make one blockchain transaction, it’s unlikely to be identifiable as you. If you make two, suddenly you’re getting into a lot more possible re-identification material. And then, if you have a long life on the blockchain, where you do lots of things over years and years, and something happens that unmasks something a long time ago—say, someone is arrested and they disclose records of which people were associated with which wallets—now a bunch of your transactions are in the public domain, even if you weren’t doing anything illegal.

Did you have fun writing about crypto?

A little bit. Crypto is weird, because, much more so than other technologies, if you don’t like crypto, crypto people really want to convince you that you’re wrong. There are other technological choices that I’ve been involved with. Like, for example, I think that the iOS model of curated computing, where a company not only has its own app store but stops you from choosing a rival app store—I think that’s bullshit. And there are a lot of people who really like Apple, and yet very few of them insist that I come on their podcast to explain why I think they’re wrong. And I had to declare a moratorium on going on blockchain podcasts to explain why I thought people were wrong. There is, among blockchain enthusiasts, a kind of unwillingness to believe that, if someone disagrees with you, it’s because they understand you and, despite understanding you, still disagree.

Ethereum is a project based around decentralized applications, which run on a scattered network of computers and don’t have a single owner who controls them. That would seem to be in line with what you want for the Internet, in the sense of more interoperability and more security. Or am I wrong?

I think distributed apps are a great idea. I am skeptical of smart contracts, which are the building block of distributed apps. Smart contracts are hard to get right. And this is not a thing that you can fix. There’s this foundational idea in computer science called the halting problem, which says that, above a pretty minimal threshold, it’s impossible to know all the different ways that a program can behave. One of the ways that computer scientists try to address this risk is by keeping Undo buttons around in our code. We try not to make irreversible operations. We try to write a backup of the data before we save it again, so that, when you save it, if the program crashes, you have a backup of the last save state. We try to maintain an audit log and to unwind processes that go off the rails.

The code in your anti-lock braking system, though—once it fails, your brakes don’t work, and that’s it. You can’t unring that bell. Or the code that controls whether or not the coolant will be released into the nuclear reactor—if it fails to go off, and the reactor melts down, you can’t fix it. Those are still instances where we want automation, and we try to minimize how automated they are, and we try to surround them by other systems—we try to build, like, soft walls around them, because we understand that this should be the exception, and it should be treated as very dangerous, because computer programs are very unpredictable.

In blockchain land, including in smart-contract land, we throw all of that away. We take applications that in no way benefit from being irreversible and we make them irreversible. So, rather than having a bank that decides whether or not a transaction goes forward, you have this automated Proof of Work or Proof of Stake process, all these different computers, running in tandem, all checking each other’s work, and there’s no way to unwind it.

The title “Red Team Blues” plays on an idea from cybersecurity and war gaming, that red attacks and blue defends. The red-versus-blue concept comes up at different points in the narrative. Was it a structural cornerstone for the book from the beginning?

In some ways, it’s just me working out my own anxieties. I am firmly convinced of the attacker’s advantage—that the attacker needs to find one exploitable defect, and the defender needs to make no mistakes. And this means that, over the long term, attackers tend to have the advantage, and defenders need to become attackers in order to win. But, at the same time, it makes me despair for some of the things that I treasure. Like content moderation, for example.

I worry that, because of the attacker’s advantage, the people who want to break the rules are always going to be able to find ways around them, and that we’re never going to be able to make a set of rules that is comprehensive enough to forestall bad conduct. We see this all the time, right? Facebook comes up with a rule that says you can’t use racial slurs, and then racists figure out euphemisms for racial slurs. They figure out how to walk right up to the line of what’s a racial slur without being a racial slur, according to the rule book. And they can probe the defenses. They can try a bunch of different euphemisms in their alt accounts; they can see which ones get banned or blocked, and then they can pick one that they think is moderator-proof.

Meanwhile, if you’re just some normie who’s having racist invective thrown at you, you’re not doing these systematic probes—you’re just trying to live your life. And they’re sitting there trying to goad you into going over the line. And as soon as you go over the line they know chapter and verse. They know exactly what rule you’ve broken, and they complain to the mods and get you kicked off. And so you end up with committed professional trolls having the run of social media and their targets being the ones who get the brunt of bad moderation calls. Because dealing with moderation, like dealing with any system of civil justice, is a skilled, context-heavy profession. Basically, you have to be a lawyer. And, if you’re just a dude who’s trying to talk to your friends on social media, you always lose. So this book is me trying to work out what it means to be on the red team—or, rather, to be forced onto the blue team when you want to be on the red team, and how you can turn the tables…

Good stuff.

SUMMARY RECAP

UPDATE

Reported by Yahoo Finance:

The judge who presided over the criminal fraud trials of Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes and her co-defendant and one-time boyfriend, Theranos COO and president Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, sentenced Balwani on Wednesday to nearly 13 years in prison plus three years of probation...I'm OK with that. Given the length, it's not gonna be Club Fed. Looks like he'll serve not quite 11 years, net (federal system). I don't wish him any harm. You properly go to prison as punishment, not for punishment.

OK, BACK TO THE BEAST

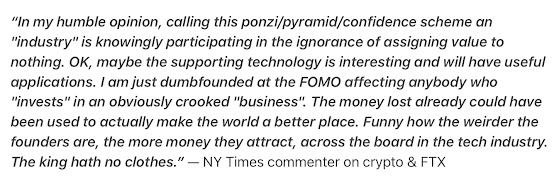

Scary to realize that someone so inept and so full of shit could gain access to billions of dollars of others' actual money—which he then made disappear, either through negligence or nefarious intent.

__________ #cryptNOcurrency

No comments:

Post a Comment