"Rethinking reproductive harm."

Got my latest issue of Science Magazine.

As per custom, I scan the Table of Contents, and head straight for the book reviews. Found this (among others).

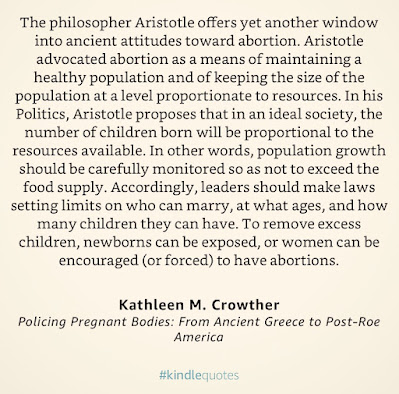

In her new book, Policing Pregnant Bodies: From Ancient Greece to Post-Roe America, Crowther explains that “although our current biomedical understanding of pregnancy and fetal development is relatively new…many of our most cherished ideas about reproduction trace their origins back thousands of years.” Crowther believes that we must examine the long history of ideas about pregnant people, fetuses, pregnancy, and abortion to understand where we are now. She does not trace a direct line of influence from the ancient world to today—an impossible task— but she effectively shows how the same misogynistic ideas crop up repeatedly throughout history, pitting pregnant people against fetuses in a dangerous zero-sum game…

In Policing Pregnant Bodies, Crowther combines three decades of experience as a medical historian with a rare ability to communicate clearly and engagingly with a general audience. She also brings her personal experience of living in Oklahoma— “one of the reddest states in the country”—to bear. In 2021, Oklahoma passed House Bill 2441, banning abortion after 6 weeks of pregnancy. When women in the state miscarry and seek medical attention, they can be arrested for manslaughter. But Oklahoma also has some of the worst infant and maternal mortality rates in the country. Fifty-four of its 77 counties contain food deserts. Active fracking sites in the state pollute the water supply, substantially increasing the risk of miscarriage. Policies such as House Bill 2441, Crowther writes, “treat pregnant people themselves as the greatest threat to fetal life,” while doing nothing to address factors that play a far greater role in infant and maternal mortality, including lack of access to healthy food, clean water, safe housing, and medical care.

THE REVIEWS

Timely and important.This book is a wake-up call for those who care about and for women and children.

— Library Journal (starred review)

Historian Kathleen Crowther sees a connection between Ancient Greek philosophers studying embryos and modern day abortion restrictions....In her new book, Policing Pregnant Bodies...Crowther examines ancient metaphors that are still being used, describes the process through which early physicians came to understand fetal development, and explores the pernicious notion that a pregnant woman is the primary threat to the health of her fetus.

— NPR

[Crowther] effectively shows how the same misogynistic ideas crop up repeatedly throughout history, pitting pregnant people against fetuses in a dangerous zero-sum game....In Policing Pregnant Bodies, Crowther combines three decades of experience as a medical historian with a rare ability to communicate clearly and engagingly with a general audience.

— Science

This book is a masterpiece. Though the medical and legal surveillance of pregnant women's bodies is relatively recent, Crowther demonstrates how wombs have historically been considered dangerous places and how the policing of pregnant bodies today is an insidious extension of that train of thought. The explicit links that she draws between the present and the past are the brilliant foundation of this perceptive historical analysis.

— Elizabeth Reis, Macaulay Honors College, City University of New York, author of Bodies in Doubt: An American History of Intersex

There's a long history of showing the fetus as independent, with the body of the person carrying it as passive, or even hostile. This lively and readable introduction shows how historical metaphors of pregnancy can help us understand modern preoccupations with saving babies rather than supporting women.

— Helen King, The Open University, author of Hippocrates' Woman: Reading the Female Body in Ancient Greece

A timely, important intervention that reveals the long histories of many of our modern ideas about reproduction. In our time of reproductive health crisis in the United States, this book illuminates the ways in which ideas about women as threats to fetuses or about inherent conflict between fetuses and women are neither natural nor inevitable.

— Julie Hardwick, University of Texas at Austin

While fetal monitors and ultrasounds seem to define pregnancy today, Crowther reveals that our ideas about the relationship between fetus and pregnant person are profoundly shaped by very old ideas about procreation. Incisive and elegant, this critical commentary is urgent reading in our current moment.

— Mary Fissell, Johns Hopkins University

From Aristotle to 21st-century statehouses, Crowther excavates the embryologic origins of symbolics of the fetus and the pregnant body that now dominate medical, political, and popular discourse around abortion and pregnancy in the U.S. Essential reading for anyone interested in how a range of policies harm the well-being of babies and birthing people.

— Carolyn Sufrin, author of Jailcare: Finding the Safety Net for Women Behind Bars

In this compelling, accessible history of embryology, pregnancy, and its interruption, Crowther reveals the development of ideas that have led to pregnant persons' rights to bodily autonomy being diminished, denied, even condemned. With nuance, Crowther puts past and present into dialogue to expose a history of insidious ideas that continue to shape our present.

— John Christopoulos, author of Abortion in Early Modern Italy

Yep. Based on what I’ve read this far, those plaudits are entirely warranted.

As a male, I am always troubled by the feeling that I have no right to even an opinion on issues of womens' reproductive decisions. An individual woman's prerogative to reproductive autonomy is properly inviolate.

Nonetheless, I share a relevant story from one of my other blogs. It's not an abstraction for this male.

The year is 1969, the place, suburban Seattle. A young couple chafes within the throes of an ill-advised (and ultimately doomed) marriage. They have an infant girl, on whom the young father joyfully dotes. The one unequivocally bright spot. Parenthood, at least, suits him, so it seems.The foregoing is no mere illustrative fictional anecdote conjured up for emotional impact. I am that father.

The young wife announces one day that she is again pregnant. But, while the husband is thrilled at the news, she exudes an inexplicable anxious and distant air. In the subsequent weeks, her smoldering anxiety morphs into a controlled state of cornered panic, and the devastating truth must finally be aired one night; she had had a recent transient sexual dalliance, and this unwanted pregnancy is almost certainly the upshot. To make matters even more complex, the cuckolding paramour is a black man (this couple is white).

Thermonuclear agonies ensue, regarding which, words utterly fail.

The young woman is beyond frantic to obtain an abortion (circumstances being exacerbated by the fact that her own father is an overt racist), but, this being an era prior to Rove vs Wade, abortions are proscribed by law in Washington state. Her subsequent attempts to procure one illegally fail, and she realizes she will have to carry this fetus to term.

She is then advised by state social services agencies that she may indeed relinquish the newborn sight-unseen for adoption, and wishes to opt for that alternative to end this nightmare, however imperfectly. This, though, requires the husband's written assent, which, for reasons not entirely clear to him, he declines to provide. In part, one can safely assume, hoping against hope that this is all a cruel, horrific dream, and the child will in fact prove to be biologically his.

An uneventful delivery obtains in the hospital in Renton in July of 1970, a 7 lb. 6 oz. healthy baby girl. The young man hesitantly approaches the glass partition of the nursery unit. The moment of truth in a glance: 'Nope, well, this is definitely not your child.' A fleeting, wracked feeling of being dropped down an open elevator shaft gives way within seconds to a subsequent flustered internal flurry: 'Now what? Whatever will become of this child? None of this shit is her fault...'

He turns and heads down the hall to the office, whereupon he signs the requisite parental paperwork. He will be her "father." Not even legally her "adoptive father," simply her father, DNA be damned. His bigoted father-in-law be damned. Subsequent hushed gossip and furtive glances within his social cohort be damned.

Fast forward four years to a Clark County, Washington courtroom. The young man is granted an uncontested divorce, along with sole custody of his two girls. The henceforth ex-wife does not attend the hearing.

Fast forward yet again. Knoxville, Tennessee a decade later, a dining room discussion ensues during which the younger daughter learns for the first time the full story."Thanks, Dad, you saved my life."

They laugh. It is good.

Nonetheless, it is not my place to dictate to women what they must do should they become pregnant.

______

DR. CROWTHER

INTRODUCTIONI'm deep into it. Had not been on my on-deck list. Compelling. No man could write this.

In popular pregnancy guides, cutting-edge medical research, and pro-life propaganda, fetuses are treated as separate and distinct from the people whose bodies they inhabit. Fetal development has been mapped in exquisite detail from fertilization to birth. Pregnant people, on the other hand, are little more than incubators, and faulty ones at that, requiring constant supervision to prevent them from harming the fetuses they carry. To this day, many aspects of pregnancy are poorly understood, and many obstetricians are not trained to recognize and treat serious complications like preeclampsia and infection, especially when they occur after the birth. The combination of fervent concern for the well-being of fetuses and hostility to pregnant people has been disastrous for both.

Although our current biomedical understanding of pregnancy and fetal development is relatively new, dating back to the mid-twentieth century, many of our most cherished ideas about reproduction trace their origins back thousands of years. A great deal of what we know or think we know about procreation owes more to ancient religion and philosophy than it does to modern science…

We describe pregnancy as passive, not active, something that happens to women, not something that women do. This mindset has consequences. An artist needs social, emotional, and financial support to create works of art. Your oven does not need social, emotional, and financial support to bake bread. “A bun in the oven” might seem like a perfectly innocent expression, just a quaint and old-fashioned euphemism for pregnancy, but it is part of a broader pattern of thinking about reproduction that we have inherited from the ancient world, and one that continues to shape the ways we treat pregnant people. Nowhere is the influence of ancient ideas about reproduction more apparent that in our contemporary debate about abortion.

On January 22, 1973, the US Supreme Court handed down its decision in Roe v. Wade, declaring a Texas law prohibiting abortion, and similar laws in other states, to be unconstitutional. Chief Justice Harry Blackmun (1908–1999), writing for the majority, argued that the “right to privacy” guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment was “broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” This right was not absolute. States had an “important and legitimate interest in protecting the potentiality of human life.” However, the state’s interest in potential life—in the fetus—could not override a woman’s right to an abortion until viability, the point in pregnancy when the fetus was capable of “meaningful life outside the mother’s womb.”…

Not quite fifty years later, on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned the Roe decision. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the court declared: “The Constitution does not confer a right to abortion.” Justice Samuel Alito (b. 1950), writing for the majority, asserted that “the viability line [established by the Roe decision] makes no sense.” There was no reason that a state’s interest in the protection of “potential life” could not begin well before viability. Each state should be able to determine for itself if and when abortion was legal. In anticipation of the court’s decision, thirteen states had already passed “trigger laws” banning abortion that automatically went into effect. Most of these laws ban abortion any time after fertilization. Politicians in some states have signaled their intent to introduce legislation banning or restricting abortion. Leaders in other states have affirmed their commitment to maintaining legal abortions…

As our awareness of and concern for fetuses have increased in the years between Roe and Dobbs, so too have our suspicions about and surveillance of pregnant people. In recent years, states have prosecuted women for using illegal drugs while pregnant, even if their babies were born healthy. Doctors and midwives have violated patient confidentiality to inform police of illegal drug use by pregnant patients. Hospitals have tested newborns for drugs and reported findings to the police. Doctors have obtained court orders forcing women to undergo Caesarean sections and other invasive medical interventions, on grounds that such interventions were in the best interests of the fetus. In such cases, laboring women have been denied the right to make their own medical decisions. Perhaps most cruelly, states have prosecuted women who miscarried or gave birth to stillborn babies, even when these women had no intention of ending their pregnancies. All of these trends reflect the insidious idea that the fetus requires special protection from the mother. In the interests of “protecting” the fetus, the mother’s rights to privacy and bodily autonomy can be abrogated…

Since Roe, the maternal mortality rate in the United States has risen, and it is now among the highest in the industrialized world. The infant mortality rate has also risen disastrously. Concern for “potential life” could, in principle, lead to better conditions for pregnant or potentially pregnant people. We could, as a society, make it a priority that all pregnant people and all who could become pregnant have access to healthy food, clean water, safe housing, and medical care. We could guarantee these things to all fetuses when they are born. But we do not. Instead, we treat pregnant people themselves as the greatest threat to fetal life. To protect fetuses, we ban abortions, regulate the behavior of pregnant people, and punish them for miscarriages and stillbirths. Our beliefs, attitudes, and policies surrounding reproduction are not saving babies, and they are harming women…

Crowther, Kathleen M. Policing Pregnant Bodies. Johns Hopkins University Press. Kindle Edition [loc 51-165].

See some of my prior blog rants related to Dobbs.

|

| click |

[Nov 8th, 2023] Former Senator Rick Santorum complained that the major election losses Republicans suffered are actually a sign of how “pure democracies” are a bad form of government.

Republicans faced devastating losses on Tuesday, as voters in Ohio overwhelmingly chose to legalize marijuana and enshrine abortion rights in the state Constitution. In Virginia, Democrats flipped the state House of Representatives, taking control of the entire legislature. While abortion was not explicitly on the ballot, the future of reproductive rights in Virginia hinged on which party controlled the government.

“You put very sexy things like abortion and marijuana on the ballot, and a lot of young people come out and vote. It was a secret sauce for disaster in Ohio,” Santorum whined Tuesday night on Newsmax…

The arrogance.

DR. CROWTHER

CONCLUSION

I began writing this book when Donald Trump was president. It was clear from the day of his surprise victory over Hillary Clinton that reproductive rights were in danger. A substantial portion of Trump’s base were (and are) evangelical Christians who expected him to abolish legal abortion. During his presidency, pro-life politicians and activists were emboldened to push for more restrictive abortion laws in many states. These included “heartbeat laws” that ban abortion after a fetal “heartbeat” is detected and “fetal personhood laws” that define a fertilized egg as a human being. These laws do not just ban abortion, they also justify the regulation of pregnant people and the criminalization of actions perceived as detrimental to the fetus. As Alison McCulloch writes, “Once you have a citizen, a person, living inside you, with all the rights and moral status that citizenship and personhood attract, then the authorities gain the right of entry, and a regulatory role in how that fetal citizen is treated.”1 In the interests of “protecting” the fetus, the mother’s rights to privacy and bodily autonomy can be abrogated. Trump’s appointment of two Catholic pro-life judges to the US Supreme Court put the final nails in the coffin of Roe v. Wade.

Like many Americans, I could see that I was witnessing a period of rapid historical change as the rights that I enjoyed throughout my reproductive years were stripped away from my children’s generation. But as a historian who has spent the past three decades studying and teaching the history of reproduction, I could also see that I was witnessing arguments and ideas that were very old indeed. Although heartbeat laws and fetal personhood laws are specific to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, I often experienced a sense of déjà vu when I read or heard support for these bills. [pp.203-204]

Below, I post this to my social media every Mother's Day.

UPDATE

Nov 9th. Very interesting.

THE NEW GOP HOUSE SPEAKER

|

| Click for tweet link. |

Yeah, women are simply broodmares. Moreover, Speaker Johnson would surely expediently agree with Aristotle that offspring are the property of the state, not the mother. Modern economic imperatives provide his modern rationale. Reverence for fetal personhood is just so much sanctimonious window-dressing.

UPDATE

I finished the book this afternoon. Totally 5 Stars, both in terms of engrossing relevant scholarly historical detail and elegant writing style. Again, no male could have written this book. ALL males (and women) should read it closely.

DR. CROWTHER CONCLUDES

I noted at the beginning of this book that it was not a comprehensive history of embryology. I chose to focus on aspects of that history that were relevant to contemporary issues, but also ones that display the continuities between the past and the present. Another value to studying history is that we encounter ways of thinking that are different from our own. Examining unfamiliar ideas about procreation can cast new light on our own assumptions. For example, based on her analysis of seventeenth-century English medical texts, historian Mary Fissell found that many English people in this period imagined the fetus “as a sort of guest within the mother’s body, and it was her job to provide appropriate hospitality to it, just as she would in her own home.” In this metaphor, “women’s bodies were naturally welcoming and generous.” This way of thinking about pregnancy is, as she points out, strange to modern readers. We are far more accustomed to metaphors that imply that pregnant women’s bodies are passive. And, as I have demonstrated in this book, we have deeply ingrained fears of the dangers posed to the fetus by the pregnant woman.__________

The implication of saying a woman has a “guest in her house” is very different than saying she has a “bun in the oven.” Taking care of a guest is work, but it is work that one undertakes willingly and (ideally) lovingly. If you are forced to take someone into your house and care for them, they are not a guest. Hospitality is also embedded in notions of community, reciprocity, and mutual obligations. By contrast, the metaphor of the bun in the oven implies that the womb is nothing more than a heat source. The real work of creating the fetus has already been done by the father. The point is not that one metaphor is more “accurate” than the other—both capture some aspects of pregnancy and ignore others. The point is that the “guest in the house” metaphor forms the basis for a more positive view of pregnancy, and of the pregnant woman, than does the “bun in the oven” metaphor. If we thought of women’s bodies as inherently nurturing, rather than inherently dangerous, we would be less likely to blame and to punish women for poor pregnancy outcomes. If we thought of pregnancy as creative work, rather than incubation, we would be more likely to support and nurture pregnant people. Policing Pregnant Bodies [pp. 207-208]

No comments:

Post a Comment